Fission may fizzle as nuclear power reacts to economics

April 3, 2015

By Ryan Holeywell

Houston Chronicle

Excerpt:

"This is the best the 1970s had to offer," says James Von Suskil, vice president of nuclear oversight for NRG Energy, one of the owners of the plant in Matagorda County 80 miles southwest of Houston. Some components on the control panel are so old that the plant operators look to the auction website eBay for parts.

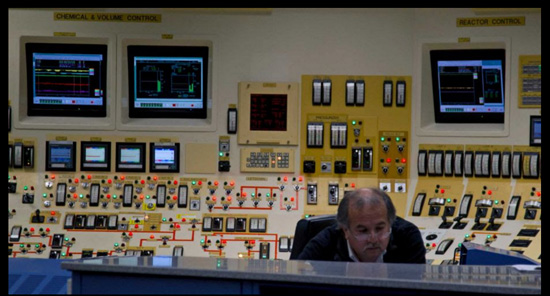

An operator works in the control room of Unit 1 at the South Texas Project nuclear power plant in Wadsworth.

© 2015 Houston Chronicle Photo: James Nielsen, Staff

WADSWORTH – A panel of dials, meters and knobs surrounds the beige-colored control room at the South Texas Project, one of two nuclear power plants in Texas.

The displays that light up in bright shades of red and green have a decidedly retro look with nary a digital display in site.

"This is the best the 1970s had to offer," says James Von Suskil, vice president of nuclear oversight for NRG Energy, one of the owners of the plant in Matagorda County 80 miles southwest of Houston. Some components on the control panel are so old that the plant operators look to the auction website eBay for parts.

But the look of the control room belies the fact the South Texas Project – which opened in 1988 – is one of the newest nuclear power plants in the United States.

The nuclear industry hopes that will change – although it faces a number of obstacles.

As cutting carbon emissions becomes a priority for government and business, proponents of the nuclear power sector say their technology is the perfect way to fill a void as coal plants close under the weight of new environmental rules

But they also acknowledge that in the age of cheap natural gas, the economic headwinds might be too strong to allow a nuclear renaissance.

While officials at the South Texas Plant tout the important role of nuclear energy to the country’s energy mix, NRG has shelved plans to help finance the expansion of the facility from two units to four.

"The economics of new nuclear just don’t permit the construction of those units today," NRG spokesman David Knox said.

Nuclear energy provides nearly 20 percent of the nation’s electricity, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute, a trade group.

Texas has two nuclear plants – the South Texas Project and the Comanche Peak Nuclear Power Plant in Somervell County southwest of Fort Worth.

Combined, they provide about 12 percent of the state’s electricity- more than comes from solar and wind power combined.

But unlike those other emissions-free sources, nuclear plants almost always operate at or near full capacity, making them part of what the power industry calls the "base load."

While the nuclear power industry has long portrayed itself as a clean source of energy, it’s doubling down on that pitch as it emphasizes the role nuclear can play in meeting the country’s pollution goals. While solar and wind are important, the industry argues, they don’t operate at the same scale or as consistently as nuclear.

"I believe there absolutely is a future for nuclear energy," said Tim Powell, site vice president at the South Texas Project, during a discussion with journalists at the plant Thursday. "Any portfolio of electricity within a state needs a good mix."

The South Texas Project is owned jointly by NRG, Austin Energy, and San Antonio’s CPS Energy, and its federal licenses allow it to operate until at least 2027.

Although NRG shelved plans to help fund two additional units at the facility, it hasn’t halted the ongoing process of requesting permits for them, since it wants to allow the plant to seek another source of funding.

Knox said NRG he expects the government to grant permits for those new units sometime next year.

Whether that will translate into construction is another question, because of a slew of broader factors that nuclear advocates say threaten the future of their industry.

"When I flip the light switch, I don’t give a lot of thought to where the power comes from," said former Indiana Sen. Evan Bayh, co-chair of Nuclear Matters, a group supported by nuclear plant operators.

"But because of the trends and the risk to 20 percent of our electric supply, the public needs to start thinking about this and understanding what the challenges are."

Natural gas provides 27 percent of the country’s electricity and an even bigger share in Texas.

The domestic production boom unleashed an abundance of natural gas that has pushed its price dramatically lower than it was a decade ago, bringing electricity costs down along with it.

That means many nuclear operators have to accept lower prices for their product, despite the higher capital costs of a nuclear plant, which makes the economics of the projects harder to justify.

The industry contends that electric markets don’t price in the economic value of nuclear’s reliable, carbon-free electricity.

"People tend to take these plants for granted," Bayh said. Without a healthy nuclear industry, he argues, it will be nearly impossible for the country to meet its clean air standards.

One way to do that, he and others say, would be to add nuclear power to states’ renewable portfolio standards.

Those rules require electric producers to generate – or buy from other generators – a certain amount of electricity from renewable sources. In Texas and most other states, eligible sources include wind, solar and biomass power, but not nuclear.

"Nuclear is as clean as any of the sources in those programs," said Michael Krancer, a partner at the law firm Blank Rome and former secretary of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection.

Another hurdle for nuclear power is the largely flat U.S. electricity demand, held down by a sluggish economic recovery and increasing energy efficiency of houses and appliances.

For now at least, the industry struggles to overcome the obstacles.

The U.S. has 61 commercial operating nuclear plants, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Nuclear plants in Florida, Wisconsin and California closed in 2013, and the Vermont Yankee plant closed last December.

"They’re perfectly healthy plants, and they’re not shutting down because they’re too old," Krancer said. "They’re shutting down from unfair market competition."

Krancer argues that federal tax credits for wind power make it difficult for nuclear to compete on a level playing field in competitive electric markets.

That message falls flat among most environmental advocates. The Sierra Club, for example, says the 2011 Fukushima disaster triggered by an earthquake and tsunami in Japan shows nuclear is still too risky.

And, the organization says, the lack of a long-term federal plan on nuclear waste disposal leaves safety questions unanswered.

The Sierra Club also contends that the billions of dollars it costs to build nuclear reactors would be spent more wisely on developing renewable sources like solar and wind.

The economic hurdles facing nuclear plants are especially acute in Texas and other deregulated electricity markets, said Julien Dumoulin-Smith, a utilities equities analyst at investment bank UBS.

Large-scale nuclear plants may have cost advantages over other generation sources in the long-term, he said. But their large up-front costs and the long lifespan of their assets make the economics of the project risky, especially when power prices are relatively low.

Five nuclear reactors are under construction now at three sites, according to the Nuclear Energy Institute.

Among them is a second unit at the existing Watts Bar nuclear plant in Tennessee, which is likely to come online later this year. It will be the first new commercial reactor in the U.S. since 1996, according to the Tennessee Valley Authority.

The milestone doesn’t impress nuclear opponents.

"Nothing has changed," said John Coequyt, director of the Sierra Club’s federal and international climate campaign.

"All the environmental groups understand: nuclear isn’t a good solution to climate change. It’s too expensive and it’s too slow."

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.