Why Japan’s ‘Fukushima 50’ remain unknown

3 January 2013

By Rupert Wingfield-Hayes

BBC News, Tatsuno, Japan

The BBC’s Rupert Wingfield-Hayes has been to the radiation zone to meet one of the workers who stayed at the plant Japan quake

Entering the exclusion zone around the crippled Fukushima nuclear power plant is an unnerving experience.

It is, strictly speaking, also illegal. It is an old cliché to say that radiation is invisible. But without a Geiger counter, it would be easy to forget that this is now one of the most contaminated places on Earth.

The small village of Tatsuno lies in a valley 15km (9.3 miles) from the plant. In the sunlight, the trees on the hillsides are a riot of yellow and gold. But then I realise the fields were once neat rice paddies. Now the grass and weeds tower over me.

On the village main street, the silence is deafening – not a person, car, bike or dog. At one house, washing still flaps in the breeze. And all around me, invisible, in the soil, on the trees, the radiation lingers.

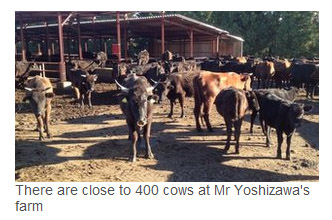

But on top of a hill behind the village is a farm – and here there is noise. Two long metal sheds are crowded with cows, nearly 400 of them. Sitting next to a wood stove sipping a cup of coffee is 58-year-old Masami Yoshizawa.

He shouldn’t be here. Nor should his cows. He should be gone and they should be dead. But Mr Yoshizawa is refusing to leave or slaughter his cows.

He shouldn’t be here. Nor should his cows. He should be gone and they should be dead. But Mr Yoshizawa is refusing to leave or slaughter his cows.

"I will never be able to grow rice again on this land," he says. "No vegetables, no fruit. We can’t even eat the mushrooms that grow in the woods; they are too contaminated. But I will not kill my cows. They are a symbol of the nuclear disaster that happened here."

From Mr Yoshizawa’s front porch, you can clearly see the tall white chimneys of the nuclear plant. Standing here, it’s easy to understand the anger and hatred people like him feel towards the Tokyo Electric Power Corporation (Tepco).

A Japanese parliamentary report published in July makes it clear that the Fukushima reactor meltdowns were not the unavoidable result of an extraordinary natural disaster. They were a man-made catastrophe, the report says.

But it is also clear the disaster would have been much worse were it not for the actions of hundreds of employees of the same Tepco.

‘Responsible’

In the immediate aftermath of the disaster, the foreign media, including the BBC, hailed the men as the "Fukushima 50".

The Tepco workers have remained largely unknown during the crisisIn fact there were never 50 of them. Hundreds of workers stayed at the plant, braving high levels of radiation to bring the reactors under control. Many are still there today.

The Tepco workers have remained largely unknown during the crisisIn fact there were never 50 of them. Hundreds of workers stayed at the plant, braving high levels of radiation to bring the reactors under control. Many are still there today.

And yet almost nothing has been heard from them. No awards, no newspaper articles or TV interviews. We don’t even know their names.

It took us weeks to track one man down and persuade him to talk to us. Even then, he insisted we could not photograph him or use his name.

We meet on a rainy day at a Tokyo park, far away from any crowds. The young man describes how he and a group of other nuclear workers were sent back in to the plant after the first reactor explosion.

"The person who sent us back didn’t give us any explanation," he says. "It felt like we were being sent on a death mission."

I put it to him that what he and his colleagues did was heroic, that they should feel proud. He shakes his head, a slightly anguished look on his face.

"Even when I’m out with friends, it’s impossible to feel happy. When people talk about Fukushima, I feel that I am responsible."

‘Mulitiple stresses’

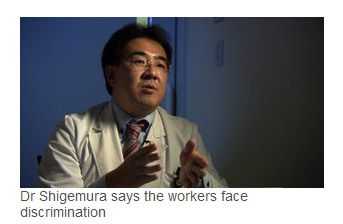

For an outsider, such a reaction is quite hard to fathom. For help, I turn to psychiatrist Dr Jun Shigemura at Japan’s national defense university. He is one of two doctors who have studied the Fukushima workers.

His research suggests that half of those who fought the reactor meltdowns are suffering from depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms.

"The workers have been through multiple stresses," Dr Shigemura says.

"They experienced the plant explosions, the tsunami and perhaps radiation exposure. They are also victims of the disaster because they live in the area and have lost homes and family members. And the last thing is the discrimination."

Yes, discrimination. Not only are the workers not being celebrated, they are facing active hostility from some members of the public.

"The workers have tried to rent apartments," says Dr Shigemura. "But landlords turn them down, some have had plastic bottles thrown at them, some have had papers pinned on their apartment door saying ‘Get out Tepco’."

‘Not heroes’

Back in the 1960s and 70s, getting rural Japanese communities to accept nuclear power plants was hard.

Dr Shigemura says the workers face discriminationThey were promised new roads and sports facilities. They were promised high paying jobs in the plant. And most of all, they were promised that nuclear power was completely safe.

Dr Shigemura says the workers face discriminationThey were promised new roads and sports facilities. They were promised high paying jobs in the plant. And most of all, they were promised that nuclear power was completely safe.

Now that the lie has been so tragically exposed, the feeling of betrayal is huge.

Before the meltdowns, Seiko Takahashi never thought of activism. Now the middle-aged mother from Fukushima City is a passionate anti-nuclear campaigner. And she admits there is little sympathy for the Fukushima workers.

"They are not heroes for us," she says. "I feel sorry for them, but I don’t see them as heroes. We see them as one block, they work for Tepco, they earned high salaries. The company made a lot of money from nuclear power, and that’s what paid for their nice lives."

And that is the final point. Japan is a country where people identify very closely with the company they work for. People here will often introduce themselves with their company name first, and their own only second.

But those close ties between the Fukushima nuclear workers and Tepco are exacting a terrible psychological toll on the men who saved Japan from a much worse nuclear disaster.

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.