Archive for the ‘WCS’ Category

Should Texas become the national dumping ground for Toxic Mercury?

At a site right next to radioactive waste?

Texas is already under assault from toxic mercury from coal burning power plants which spewed over 11,000 pounds into our air in 2007. Our children are at risk for permanent brain damage from mercury exposure and we rank worst in the nation for coal plant emissions.

Now the US Department of Energy (DOE) wants to dump on Texas and make us the national dumping ground for stored toxic mercury. It’s good to get the mercury out of circulation, but it could be stored at various sites, as opposed to all in one place. There are many viable sites that have military security and some already store mercury.

DOE wants to send up to 11,000 tons of toxic elemental mercury to the Waste Control Specialists (WCS) dump site near the Texas/New Mexico border in Andrews County Texas, DOE’s preferred site out of eight under consideration.

The WCS site is licensed to take hazardous waste. They already have highly radioactive "K-65" weapons waste from Fernald. They’re licensed to take over 59 million cubic feet of radioactive waste.

The March 20, 2010 Andrews County meeting began with a presentation by DOE’s David Levenstein. DOE relied on documents provided to them by Waste Control Specialists, as opposed to their own independent studies. They stated that there is no water under the site where the mercury would be stored. This completely flies in the face of documentation by former TCEQ employees who are concerned that groundwater is only 14 feet below the nearby trenches where radioactive waste would be stored. Mercury vapors could cause serious health impacts, including deaths. There is a risk of groundwater contamination. The Ogallala Aquifer underlies eight states in the wheat and soy growing region of the US.

Microbeads of mercury can condense on the storage canisters. 3 liter size flasks (76 pounds) would be used for the mercury in addition to 1000 pound containers.

The building would be made of sheet metal, which would probably not hold up well in a tornado. There have been 21 tornadoes in the past four decades. Mercury spewed across the region would be a disaster. Andrews County is 40% minority and 17% below poverty levels. How’s that for environmental justice?

WCS is owned by Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons, who was recently reported to be worth $3.9 billion. He wants Andrews County to provide $75 million for his radioactive waste dump. Maybe he could pull it out of his own pocket? Then again, the plan may be to strap the County with liability through the bond process and leasing buildings that the County would own. What happens if WCS goes broke later? Who pays for the clean up of hazardous waste, toxic mercury or radioactive waste if accidents or natural disasters occur?

Elemental mercury effects – This is what the EPA has to say…

Elemental (metallic) mercury primarily causes health effects when it is breathed as a vapor where it can be absorbed through the lungs. These exposures can occur when elemental mercury is spilled or products that contain elemental mercury break and expose mercury to the air, particularly in warm or poorly-ventilated indoor spaces. The first paragraph on this page lists the factors that determine the severity of the health effects from exposure to mercury. Symptoms include these: tremors; emotional changes (e.g., mood swings, irritability, nervousness, excessive shyness); insomnia; neuromuscular changes (such as weakness, muscle atrophy, twitching); headaches; disturbances in sensations; changes in nerve responses; performance deficits on tests of cognitive function. At higher exposures there may be kidney effects, respiratory failure and death. People concerned about their exposure to elemental mercury should consult their physician.

Additional information on the health effects of elemental mercury is available from the IRIS database at http://www.epa.gov/iris/subst/0370.htm.

Speak out Against Dumping Toxic Mercury on Texas!

Comments on the DOE mercury plan will be accepted until March 30, 2010.

March 30 is the deadline to comment on the Draft Long-Term Management and Storage of Elemental Mercury Environmental Impact Statement

Ways to comment include:

- Toll Free Fax: 1-877-274-5462

Send a free fax letter now!

- U.S. Mail:

Mr. David Levenstein

EIS Document Manager

U.S. Department of Energy

P.O. Box 2612

Germantown, MD 20874

More Information:

- Major Aquifer map of Texas – Texas Water Development Board, September 1990. Note – We have marked the location of the WCS facility.

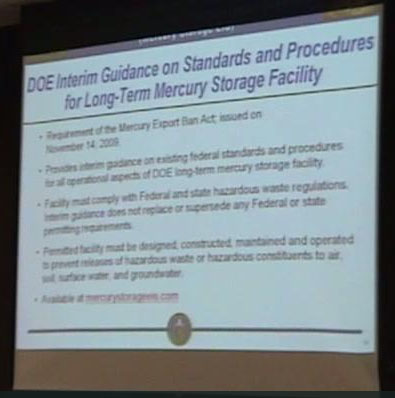

- The Environmental Impact Statement is online at: http://www.mercurystorageeis.com/library.htm

Both a summary and the full document are available.

Protect Texas from Becoming Nation’s Radioactive Waste Dump

For Immediate Release:

January 22, 2010

Contact:

Karen Hadden, SEED Coalition, 512-797-8481

State Representative Lon Burnam Asks Tough Questions of Compact Commission

Austin, TX Today State Representative Lon Burnam (District 90, Ft. Worth) called on the Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission to answer tough questions regarding their proposed rule that would open Texas up to becoming the nation’s radioactive waste dump. The Compact includes only the states of Texas and Vermont, but the draft import/export rule that is prime on today’s agenda essentially invites with open arms radioactive waste from the rest of the country and possibly the world. The waste would go to a site in Andrews County in West Texas that is owned by Waste Control Specialists (WCS).

“Turning Texas into the nation’s radioactive dumping ground so that WCS can make billions of dollars is irresponsible, especially since it will endanger public health and vital groundwater resources for thousands of years to come” said Representative Burnam. “Strong controls must be adopted now.”

“The Compact was formed to manage low-level radioactive waste generated in the Compact states, Texas and Vermont, so why is the Commission developing rules to import waste from around the country?” asked Representative Burnam, as he began with ten hard-hitting questions regarding the draft rule.

Texas and Vermont, the only two Compact parties, have expressed a need to dispose of at least 6 million cubic feet of radioactive waste in the next 50 years. Yet this volume, estimated by the Texas Compact Commission, is nearly three times more than the capacity of the site.

“If the Commission develops a rule for import, isn’t the Commission making the explicit assumption that the capacity of the site will be expanded and that the license will be amended for expansion? How can the Commission make such an assumption without a technical review of the site?” inquired Representative Burnam. He expressed concerns as to how the Commission can reconcile the discrepancy between Texas and Vermont’s estimated disposal needs and the stated capacity of site.

The State of Texas becomes liable for radioactive waste as soon as it comes across the border into our state and nuclear energy expert Dr. Arjun Makhijani has stated that increased environmental impacts would result from importing radioactive waste from outside of the Compact. Leaks from the dump site could lead to health threatening radioactive contamination. With significant potential impacts the rule should be considered a ‘major environmental rule’ and Burnam inquired as to why the Commission has not deemed it so, and then asked, “Why does the Commission not discuss the liability implications for Texas resulting from the import rule?”

Representative Burnam and safe energy advocates are calling on the Compact Commission to exercise its power and authority to protect and promote the “health, safety and welfare” of Texans as the law requires. The Commission should not allow waste to be imported from outside Texas and Vermont and should prevent Texas becoming the nation’s radioactive waste dumping ground.

The Compact meeting will be streamed live at: www.house.state.tx.us/fx/av/live/extlivecmte24.ram

Representative Burnam’s ten questions, SEED Coalition’s Comments on the draft rule, and supporting expert analysis are available online at www.nukefreetexas.org. SEED Coalition’s comments are endorsed by Public Citizen, Environment Texas, Nuclear Information and Resource Service, WE CAN, No Bonds for Billionaires and the South Texas Association for Responsible Energy.

Radioactive Waste Commission Punts

December 11, 2009

Forrest Wilder

Forrest for the Trees

Texas Observer Blog

After two days of often-contentious hearings, the compact commission postponed a decision on rules governing the import and export of radioactive waste to and from Texas.

The decision to put the vote off for 30 days came this afternoon after dump opponents as well as two commissioners, Bob Gregory and Robert Wilson, expressed concern that the rules were being rushed.

For those of you just tuning in, the Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission (try to say that all in one breath) is beginning to tackle the contentious issue of whether to allow Waste Control Specialists, a politically-connected company building a large radioactive waste dump near Andrews, to import radioactive waste from other states.

(Texas and Vermont are the only two states that have an automatic right to bury their radioactive waste at the Andrews dump.)

As commission chairman Michael Ford pointed out they’re only at the point of figuring out how that process will work; decisions about particular import petitions will be made at a later date. Still, Waste Control is eager to speed the process along, telling the commission today and yesterday that the financial survival of the company is at stake.

On the other hand, dump opponent Karen Hadden, executive director of the Sustainable Energy and Economic Development (SEED) Coalition, blasted the proposed language as "an open-ended invitation" to bury waste from around the nation.

Glenn Lewis, a former TCEQ employee, was even more expansive. "I would be reticent, I would be hesitant, I would be circumspect about allowing anyone to put radioactive waste in that hole," he said. "It will leak."

Lewis was one of several TCEQ employees who quit the agency over the upper management’s decision to issue licenses to Waste Control. As Lewis testified, the technical team reviewing Waste Control’s proposed site had concluded that the dump was perilously close to two water tables and was highly likely to leak.

But criticism from Commissioner Wilson was perhaps more unexpected.

Wilson said that comments made yesterday by Waste Control Specialists CEO Rod Baltzer that the Andrews dump was a "national solution" had upset him.

"I’m not at all sure that the state of Texas… bargained for that in 1993," said Wilson, referring to the year that the Texas-Vermont compact law was passed.

Indeed, Waste Control is already proposing to increase the capacity of the compact portion of their dump almost five times over, from 2.3 million cubic feet to 10.8 million cubic feet. Without a bigger landfill that could take radioactive materials from around the country, Waste Control has suggested they could go out of business.

Wilson said he didn’t appreciate being threatened.

"That puts an ungodly amount of pressure on us," he said.

NOTE: There were some other interesting developments at the hearing. I will have more early next week.

Stop Texas from Becoming the Nation’s Radioactive Waste Dump

For Immediate Release:

December 10, 2009

Contacts:

Karen Hadden 512-797-8481 Sustainable Energy & Economic Development (SEED) Coalition

Diane D’Arrigo 301-270-6477 Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS)

Cyrus Reed 512-740-4086 Lone Star Sierra Club

Download press release in pdf format for printing.

Austin, TX Today the SEED Coalition, Public Citizen, Lone Star Sierra Club, and Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) called for action to prevent West Texas from becoming the nation’s radioactive waste dump. The Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is holding a stakeholder meeting today. Texas and Vermont are the only two states in the Texas Compact. Prime on the meeting agenda are rules for importing “low-level” radioactive waste from states outside the Compact to the Andrews County site in West Texas owned by Waste Control Specialists (WCS). The draft import/export rule released to the public yesterday essentially invites with open arms radioactive waste from the rest of the country and possibly the world.

“Strong controls must be adopted now that will prevent Texas from becoming the nation’s nuclear dumping ground,” said Texas State Representative Lon Burnam. “Next session, I will sponsor a bill to close the loophole in the Compact Law allowing any state to dump radioactive waste on Texas without approval by the Legislature.”

“Allowing the eight member Texas Compact Commission, six of whom are appointed by Governor Perry, to approve importation of radioactive waste into Texas is undemocratic,” said Representative Burnam. “Turning Texas into the nation’s radioactive dumping ground so that WCS can make millions of dollars is irresponsible, especially since it will endanger public health and vital groundwater resources for thousands of years to come.”

This won’t be the first time WCS has used its influence to benefit from political decisions. WCS, and owner billionaire Harold Simmons, got state law changed to allow a private company to become licensed for the disposal of radioactive waste, as opposed to requiring disposal by the state.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) technical team reviewing the “low-level” radioactive waste disposal license application unanimously recommended denial of the license because the site was unsafe for disposal of “low-level” radioactive waste. In a rare move, the TCEQ team recommended against issuing the license. Profit won out over safety concerns when TCEQ Commissioners issued the license anyway, ignoring its own scientists’ findings.

“All of the TCEQ scientists working on the license determined the geology of the site to be inadequate because of the possibility of radioactive contamination of our aquifers and groundwater,” said Glenn Lewis, technical editor for the TCEQ team that did a four-year review of WCS’ application. “Groundwater is only fourteen feet below the bottom of the radioactive waste dump trenches. Fourteen feet is not an adequate safety margin for a site that is supposed to isolate radioactive waste for tens of thousands of years, but there was pervasive political pressure throughout the entire process to issue a license to WCS regardless of how unsafe the site was.” Three TCEQ employees quit over the decision to issue the license.

Another of these employees was Encarnacion (Chon) Serna Jr., a chemical engineer reviewing several sections of the application, who resigned after it became apparent that the licenses were going to be granted by TCEQ no matter what. Serna indicated “that even after a third (only two allowed by state rule) notice of technical deficiency was granted to the Applicant WCS, the application was still extremely deficient in what it proposed vs. what was required by state rules, not only in the areas of geology and hydrology, but also in the areas of financial assurance, engineering design, operating procedures and radioactive dose rate assessments.”

“WCS’ own data shows groundwater in and near the proposed site,” said Lewis, “If water intrudes into the landfill radionuclides could escape confinement and permanently contaminate groundwater.”

The leakage possibility is not unique to the West Texas site. “All six of the so-called ‘low-level’ nuclear dumps in this country have leaked or are leaking, often costing the states in which they are located millions of dollars,” stated Diane D’Arrigo, Radioactive Waste Project Director at Nuclear Information and Resource Service. “One of the now closed nuclear waste dumps with supposedly ‘impermeable clay’ threatens the water supply downstream and is projected to cost in the range of $5 billion to ‘clean up.'”

The draft import/export rule discusses the so-called “positive fiscal effects” from taking radioactive waste but fails to even acknowledge liability and the possible negative fiscal impacts from clean up costs that would result from radioactive leaks.

“It’s important to understand that when it comes to nuclear power and weapons waste, ‘low-level’ is not ‘low-risk,'” D’Arrigo said. “Much of the waste is dangerous now and stays dangerous for literally millions of years. Unshielded exposure to some radionuclides could kill a person in 20 minutes. Exposure to radiation causes cancer, genetic defects, reduced immunity and other health problems.”

“TCEQ rushed into a risky deal by approving a faulty application to dispose of some of the most dangerous radioactive waste known,” said Cyrus Reed, Conservation Director of Lone Star Sierra Club. “And they’ve done it without giving members of the public who are at risk a chance to prove that the application is faulty. That’s why the Lone Star Sierra Club appealed to the State District Court, asking that a hearing be required.”

“Now WCS wants to make their nuclear waste dump the nation’s radioactive waste dump,” said D’Arrigo. “The dump was only meant to take waste from five nuclear reactors in Texas and Vermont, but if the Compact Commission adopts a rule allowing ‘out of compact’ waste into Texas, the site could take waste from over 100 nuclear reactors, operating and proposed. WCS stands to profit while Texas is stuck with the long term liability and environmental devastation.”

Disposal of radioactive waste is a national and global problem, and all voices need to be heard. Texans aren’t the only ones that could be affected, as the dump is right on the Texas/New Mexico Border. “The residents of Eunice, New Mexico have been shut out of the TCEQ licensing process,” said Scott Kovac, Operations and Research Director with Nuclear Watch New Mexico. “As the closest community to the WCS site, residents of Eunice must also be included in the process.” Eunice is five miles from the radioactive waste dump.

The two parties in the Compact, Texas and Vermont, have expressed a need to dispose of at least 6 million cubic feet of radioactive waste in the next 50 years. Yet this volume, estimated by the Texas Compact Commission, is nearly three times more than the capacity of the site. The WCS license limits the total volume to be disposed at the Compact Facility to 2.3 million cubic feet. “If there isn’t room for Texas’ and Vermont’s waste, how can we even consider importing waste from out of the Compact?” said Eliza Brown, Clean Energy Advocate for the SEED Coalition. “Why should Texas be at risk of becoming the nation’s nuclear dumping ground? The Compact Commission should develop a ‘Don’t mess with Texas’ approach to radioactive waste dumping.”

WCS sought $75 million in bonds from Andrews County taxpayers, which it says it needs to begin construction of the radioactive waste dump. A lawsuit was brought by local residents, challenging the May 9th vote which was paid for by WCS. Until the questions regarding the validity of 90 ballots are resolved the county money cannot be transferred to WCS to begin construction on waste dump.

“Low-level” radioactive waste is defined as everything radioactive in a nuclear power plant except the high-level reactor fuel core. Pipes that carry radioactive water, filters and sludge from the water in the reactor, the entire reactor itself when it is dismantled (thousands of tons of contaminated concrete and steel) can all be dumped. None of the radioactive elements in high-level waste is prohibited from being included in “low-level” waste. In fact, not a single radionuclide is barred from being dumped at the West Texas site.

“We now know how the original licensing process was rushed, with a multitude of unresolved deficiencies and issues,” said former TCEQ engineer ‘Chon’ Serna. “In light of what is currently being considered by the Texas Compact Commission, it is imperative that the old unresolved issues along with the ones that were resolved as adverse to the granting of the license, be revisited, reconsidered, and resolved by an Agency Team and a Team of Experts without the political pressure of legislators and Agency Directors. If unable to resolve these issues or if further studies and investigations determine the existing site is not suited for its ‘low level radioactive waste disposal purpose,’ waste disposal on the existing site should stop immediately, existing licenses should be revoked, and no more licenses or expansions should be granted for this site.”

Texans and safe energy advocates are calling on the Compact Commission to exercise its power and authority to prohibit ‘out of compact’ waste as other compacts have done. The Commission should not allow Texas to become the nation’s radioactive waste dumping ground.

###

Good to Glow

Despite its own scientists’ objections, state regulators are greenlighting a massive nuclear waste dump in West Texas.

April 04, 2009

Forrest Wilder

Texas Observer

In February, hundreds of government regulators and businesspeople gathered in Phoenix for "Waste Management ’08," the annual radioactive waste industry confab. Amid the swag and schmoozing, industry insiders appraised the state of their business. The good news: The nuclear industry appears to be rebounding in the United States, providing potentially huge new radioactive waste streams as planned reactors come online. The bad news: The number of landfills for burying low-level radioactive waste is dwindling. One of the oldest sites, in Barnwell, South Carolina, will close to all but a handful of states on July 1. That will leave 36 states, including Texas, with no place to send the radioactive waste generated by their nuclear power plants, universities, hospitals, and companies.

Since 1980, when the federal government delegated to the states the task of dealing with low-level radioactive waste, not a single new landfill has opened. Ten attempts have been made by states to develop one. The congressional Government Accountability Office estimates that the failed efforts in developing sites cost a combined $1 billion.

The industry largely blames public opposition. "We just didn’t get kicked out of South Carolina," said Steve Creamer, CEO of Utah-based EnergySolutions Inc., the company that runs Barnwell. "We got brutalized and kicked out of South Carolina."

Creamer estimated that the United States’ 104 commercial nuclear reactors would generate 117 million cubic feet of waste over their collective lifetimes. Federal nuclear facilities under decommissioning orders will produce millions more. Where will it all go?

A subsidiary of Dallas-based conglomerate Valhi Inc., Waste Control Specialists LLC was in Phoenix to make the case that it was on the verge of doing what no other company has been able to do-license and build a massive radioactive waste landfill.

"Considering our political support, considering our local support, if a new facility cannot be licensed in Texas, it probably can’t be licensed anywhere," said Bill Dornsife, a Waste Control vice president.

By early 2010, Waste Control officials told the conference-goers, the company hopes to begin disposing federal and state radioactive waste at two adjacent Texas landfills in Andrews County. All the company lacks are two final licenses from the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. One, known informally as the "byproduct license," would authorize the disposal of 3,776 canisters of radioactive waste from a closed, Cold War-era processing plant in Fernald, Ohio, as well as mill tailings from the Texas uranium mining industry. TCEQ has issued a draft license for the byproduct dump.

The second license would allow the company to bury low-level radioactive waste from federal and state sources, including nuclear reactors, weapons programs, and hospitals. With both licenses, Waste Control could bury more than 60 million cubic feet of waste over the span of 30 years, more than half the volume of the new Dallas Cowboys stadium.

If Waste Control can repel legal challenges by environmental organizations and secure final approval from TCEQ for the second license, its remote site in Andrews County would become the repository for commercial nuclear waste from Texas, and also Vermont as part of a "compact" between the two states. A loophole in state law, however, allows the state compact commission, an oversight board appointed by Gov. Rick Perry, to contract with other states and compacts for waste disposal. "For political reasons, we don’t want anyone to come knocking on the door until we get this up and operating, but I think there are some capabilities there," Dornsife told his Phoenix audience.

Federal radioactive waste, mostly the leftovers from the U.S. government’s atomic weapons program, is the most lucrative of the waste streams contemplated by the company. In 2003, as part of Waste Control-backed state legislation that authorized privatized radioactive waste disposal in Texas, the Legislature granted companies like Waste Control the right to dispose of Cold War-era federal waste as well as waste generated by states.

"[W]e just had to get the state law changed," said Rod Baltzer, Waste Control president, at the conference. It probably didn’t hurt that Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons owns Waste Control through Valhi. Simmons is one of top campaign contributors to the state’s Republican leadership.

The new landfills would join Waste Control’s expanding waste portfolio, all of which are clustered on the company’s 1,338-acre site in Andrews County, near the New Mexico state line. The company’s radioactive waste treatment and storage plant opened in 1997. The license for that facility is "very unique," Dornsife said, because it allows for "unlimited storage time, and we could go to unlimited [radio]activity."

There’s also the hazardous waste landfill. Half of that dump is actually filled with radioactive waste, material the state has deemed "exempt" from radioactive disposal standards. The company’s efforts to broaden the exemptions are ongoing. "[D]isposing of radioactive material at [hazardous waste] pricing is extremely cost-effective," Dornsife said.

In their conference presentations, Baltzer and Dornsife failed to mention the problems the company has encountered with worker exposure to radiation. And while Baltzer admitted that the licensing process has been "brutal," he didn’t detail the rift it has created within TCEQ between scientists and engineers, who stridently object to Waste Control’s plans, and agency upper management that wants to approve the licenses.

In March 2005, Waste Control began processing radioactive waste from the Rocky Flats plant, a site in Colorado that manufactured plutonium triggers for the United States’ Cold War-era hydrogen bomb program. On June 2, 2005, while processing this waste, a worker known in state documents as Number 67 at Waste Control’s mixed waste facility was wounded on his leg by a piece of contaminated metal. The company tested the worker’s urine and feces, and found elevated levels of two plutonium isotopes, as well as americium-241. Later in June, an independent expert determined that the worker had probably inhaled the radionuclides. Over the next few months, as processing of the Rocky Flats waste continued, the investigation expanded to include eight of Number 67’s co-workers. All but one tested positive for low levels of radionuclides, including one employee who hadn’t worked at the mixed waste facility for three years. On September 22, Waste Control management decided to suspend operations at the mixed waste facility and expand the testing to virtually all employees.

In all, 43 individuals had been exposed to plutonium and americium, company testing showed, according to documents uncovered by the Observer. According to Waste Control, a ventilation system wasn’t working properly, allowing plutonium and americium particles to escape into the lunchroom and adjacent hallways.

Waste Control maintains that the radiation exposures were not dangerous. The highest calculated dosage to any employee was "less than 10 percent of the regulatory limits," according to a January 2008 Waste Control report. "We did find a handful of employees that were over our planned exposures; they were below regulatory concern," said company president Baltzer in an interview with the Observer. "We are very fastidious about applying ALARA-as low as reasonably achievable-principles. … We did note that we had some ways to improve our program. Partially as a result of this, we changed out our general manager … We think some of the employees were not as thorough in their conduct, in their operations, as they should have been."

A TCEQ audit of the company’s incident report questioned Waste Control’s dosage calculations and its handling of the situation. Waste Control officials assert that the workers were exposed to plutonium and americium-241 over a six-month period covering the summer of 2005. In contrast, the TCEQ audit, completed in spring 2007, posits that the exposures "might have been going on since 2002, at least intermittently at a minimum." The audit suggests that the company underestimated the number of batches of radioactive waste that were processed. If that were the case, the actual doses might be much higher than company reports indicate.

The audit notes that a preliminary review by John Poston Sr., a professor of nuclear engineering at Texas A&M, "suggested WCS employee doses were … seven times greater than the WCS-assigned employee doses, but still below regulatory [limits]." The agency has declined to release Poston’s complete findings.

The TCEQ audit also criticized Waste Control for waiting months to suspend operations after it learned employees had been exposed. "It is my opinion that WCS management did not act in a timely manner in their decision to suspend operations until the source of the intakes could be identified," wrote Sheila Meyers, a TCEQ chemist who authored the audit report. Baltzer said the company began testing workers as soon as possible, and temporarily closed the facility once conclusive lab results were received.

The radioactive contaminations were in large part preventable, the audit noted. Waste Control acknowledged in a report on the incident that testing employee fecal samples could have caught the exposures sooner. That failure to test may be partly the fault of state regulators. In 2003, the Department of State Health Services dropped a requirement that Waste Control test employees’ feces annually for the presence of radionuclides. Instead, the analysis could be "performed at the discretion of the [company’s] radiation safety officer."

Four male workers tested positive for radionuclides in 2007, according to TCEQ documents. One employee told inspectors in an August 2007 interview that "the air vents at the mixed waste treatment facility had not been fixed completely."

In August 2007, Susan Jablonski, the head of TCEQ’s radioactive materials division, provided her boss, Deputy Director Dan Eden, with a written update on the review of Waste Control’s two license applications. In the memo, which is stamped "confidential," she identified "radiation protection" as one of four major outstanding problem areas. "The radiation protection issues appear not to be under control at the larger site," she wrote. "The apparent loss of control of radioactive materials also impacts the ability to establish true background [radiation] at the site." Background, or natural radiation, is necessary as a baseline so that leaks can be detected.

TCEQ would not make Jablonski available for an interview. The agency did not respond to written questions before the Observer went to press.

The TCEQ hasn’t issued any violation notices to Waste Control for the radiation exposures.

There have been other accidents involving radioactive material at Waste Control’s facilities. In October 2005, two state inspectors visited the site in Andrews to investigate a string of contamination events, including the worker exposures. Their report notes three other "cross-contamination" incidents that had occurred in as many years: one involving tritium; one involving radon gas; and a leakage of americium-241 and plutonium-239 into a septic system. This string of problems "reflects either defects in ventilation scheme or inadequate administrative controls to prevent cross contamination of facilities," the inspectors wrote.

Recently, Waste Control agreed to pay $151,000 in fines to TCEQ for contaminating septic systems on two occasions, and for elevated levels of heavy metals such as arsenic, lead, and mercury at a railcar unloading area.

So far, the accidents have not derailed the company’s activities. Yet stiff resistance from TCEQ personnel in charge of reviewing Waste Control’s proposals has put the company on the defensive. One of the company’s fiercest critics, Glenn Lewis was brought on at the TCEQ’s radioactive materials division to manage any controversies concerning the application. He quickly soured on the process. "It was obvious from the beginning that the enabling legislation was written for the benefit of, and largely by, this applicant," Lewis said. "That raised immediate concerns about how objective a review of the application could possibly be." In December, Lewis left TCEQ after serving 25 years in Texas state government.

In all, three former TCEQ employees who worked on the Waste Control license applications said they left the agency because of frustration with the licensing process. All three came to the conclusion, after years of working on the applications, that Waste Control’s site is fundamentally flawed. "After years of reviewing the application, I submitted my professional judgment that the WCS site was unsuitable," said Patricia Bobeck, a hydrogeologist who worked on the byproduct application. "Agency management ignored my conclusions and those of other professional staff, and instead promoted issuance of the licenses."

Encarnación "Chon" Serna, Jr. an engineer, said he quit in June 2007 when it became apparent that a license for the low-level radioactive waste landfill would be issued despite staff objections. At the end of the staff’s technical review in August 2006, Serna and other staff members decided the application was "very, very deficient" and couldn’t be approved. Nonetheless, TCEQ mangers decided to move forward, giving the company until May 2007 to address some problem areas. "Around that time I started getting the idea that these people are going to license this thing no matter what," said Serna. "I felt that in clear conscience I couldn’t grant a license with what was being proposed."

Serna said that when he left, there were still "thousands of questions in every area of review." For example, he had trouble determining accurate calculations of radiation doses workers might expect to receive when handling soil-like "bulk waste." In 2006, Serna wrote in an internal e-mail that he’d come across 57 scenarios in Waste Control’s plan in which workers would be close to radioactive waste. "I think there could be potential exposures to significant doses of radioactivity," he wrote.

His overarching concern, shared by the other former staffers, relates to the site’s physical location. Serna said he is convinced that the geology of the site is unsuitable for containment of radioactive waste for thousands of years.

That view was echoed in an August 14 memo prepared by two TCEQ engineers and two agency geologists. The proximity of a water table to the disposal site "makes groundwater intrusion into the disposal units highly likely," the four wrote. Their memo stated that "natural site conditions cannot be improved through special license conditions" and recommended denial of the license. The next day, Susan Jablonski conveyed those concerns to Deputy Director Dan Eden, who reports directly to Executive Director Glenn Shankle. Waste Control "states the second water table is no closer than 14 feet from the bottom of the low-level landfill," read her memo to Eden, which is stamped "confidential." A staff analysis, she wrote, "shows that the water table may be closer than 14 feet."

Company president Baltzer told the Observer that the former staffers’ fears are outdated and overblown. Once Waste Control heard that staff had lingering concerns about the groundwater situation, the company began drilling new boreholes and wells to verify that water wasn’t present in or near the landfill. Waste Control has spent $3 million on the drilling and found no water, Baltzer said. "WCS’s license application demonstrates that the site will protect human health and the environment and that water will not intrude into the proposed disposal units under any credible scenario," he said.

In September, the two TCEQ teams working on Waste Control’s applications gathered to rehearse a presentation they would be giving Executive Director Shankle later that day. "The entire gist was to communicate the impossibility of licensing either facility," said Lewis, who resigned in December. "As we were adjourning, [Deputy Director] Dan Eden remarked to [TCEQ attorney Stephanie Bergeron Perdue], ‘We have to find a way to issue a byproduct license.’ This was after an hour-long presentation on why it would be unwise to issue a license for either the byproduct or low-level application."

As staff opposition grew, Waste Control took its case to the agency’s upper management. Lobbyist and attorney Pam Giblin, who represents Waste Control, met with Shankle once in September and twice in November, according to agency records. Baltzer left nine messages for Shankle and four for Eden between July 2007 and January 2008, according to phone logs that reflect only missed calls. Eden met with Waste Control officials at least five times during that period. Former Republican Congressman Kent Hance, a Waste Control investor and chancellor of the Texas Tech University System, paid a visit to Shankle’s office in early November. Cliff Johnson, a principal in Textilis Strategies, an Austin-based firm that lobbies for Waste Control, visited with Shankle in September. Shankle also met with Giblin, Baltzer, and Mike Woodward, a Waste Control lobbyist and attorney with Hance’s law firm, during that period.

The TCEQ higher-ups were in a bind: Their own technical experts had unequivocally recommended denial, and two members of the team had left in disgust. Yet the agency’s managers still wanted to push the licenses forward.

"In late October, Susan Jablonski acknowledged in writing to senior management in the agency that faulty site conditions exist and that they cannot be corrected through license conditions," said Lewis, the former staffer. "What is baffling is that Ms. Jablonski-at the same time acknowledging the inherent impossibility of correcting a bad application-still pledged to support whatever nonsensical recommendation her boss may decide to pursue."

By late October, Waste Control had a draft license in hand for its byproduct dump. TCEQ Executive Director Shankle had chosen to deal with his staff’s objections by adding stipulations to Waste Control’s licenses, including a requirement that the company conduct further studies on erosion, groundwater, and possible fractures. In March, he rebuffed the Sierra Club’s call to rescind the license. A draft license for the low-level landfill is currently being written.

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that

this constitutes a “fair use” of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted

material for purposes of your own that go beyond “fair use”, you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.