Archive for the ‘Toxic Waste Dump’ Category

High-Level Worries

Environmentalists are still fighting a dump that could bring in much more nuclear waste than originally thought.

Wednesday, 22 December 2010

BETTY BRINK

Fort Worth Weekly

By the fall of 2011, if the courts or legislators don’t act to stop it, Texas could become the "nuclear waste dump for the country if not the world," State Rep. Lon Burnam says. And he and a coalition of environmental groups are leading a last-ditch effort to stop the waste trains and trucks from rolling through Fort Worth and other parts of Texas to the site on the New Mexico border — owned by a major contributor to Gov. Rick Perry — that sits atop part of the nation’s largest aquifer.

The 1,338-acre site was licensed in 2009 with authority to accept nuclear waste from only two states, Texas and Vermont, plus "byproducts" from certain closed federal sites such as uranium processing plants. Now, however, after heavy lobbying from the dump’s Dallas billionaire owner Harold Simmons, the state’s Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is set to vote in early January on a rule that would allow the dump to throw open its gates to nuclear waste from every state.

The 1,338-acre site was licensed in 2009 with authority to accept nuclear waste from only two states, Texas and Vermont, plus "byproducts" from certain closed federal sites such as uranium processing plants. Now, however, after heavy lobbying from the dump’s Dallas billionaire owner Harold Simmons, the state’s Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is set to vote in early January on a rule that would allow the dump to throw open its gates to nuclear waste from every state.

The original license was approved by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality only after years of geological study, environmental impact statements, and public hearings. But the new rule, vastly increasing the volume of dangerous wastes moving to the site, could be approved by the waste disposal commission without any public hearings, further studies, or input beyond a 30-day comment period, which ends this week.

Karen Hadden, head of the nonprofit Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition based in Austin, is pushing her member groups to demand that TCEQ require a full environmental impact study to be undertaken before any waste crosses the Texas border. "This will have a tremendous environmental impact on West Texas and the aquifers there, and it makes no sense not to do [the environmental studies]," she said.

The granting of the original license to Waste Control Specialists, owned by Simmons, was hugely controversial. TCEQ approved the license despite vigorous opposition from the state’s own scientific experts, who found that the site was geologically unsound and would not be stable enough to protect humans and the environment, especially the Ogallala aquifer, during the hundreds of thousands of years that the wastes will be dangerous. Three TCEQ employees resigned in protest when the agency overruled their recommendation that the license be denied.

In recent months, however, the full story of that licensing process has been revealed by one of the three TCEQ employees who quit. Glenn Lewis, the technical editor of the TCEQ team at that time, is now one of the agency’s most vocal critics.

The potential for contamination of the Ogallala is real, said Lewis, and that fact was explained in detail to top TCEQ administrators and commissioners at the time.

After four years of study of the Waste Control application, the TCEQ technical team reported in a memo that because groundwater from two nearby water tables would "intrude into the … disposal units and contact the waste," the site "is not suitable for near-surface disposal of radioactive waste."

Although Waste Control Specialists claimed initially that there was at least 120 feet of "impenetrable red bed clay between the site and the nearest groundwater, the team found groundwater within 12 feet of the bottom of the storage facility," Lewis said, "too close for a facility that must contain waste for more than 50,000 years.

"It is a tenet of federal and state law that intrusions of water into buried radioactive waste must be avoided," he said. "This site does not in any way, shape, or form meet those standards." He pointed out that "low-level" does not mean "low-radiation." It can be "the most dangerous kinds of waste" from nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons programs, he said.

The West Texas site is a "nest of related holes in the ground [for burial of all of the different types of waste sent there]," he said, "and there was always standing water in the pits, seeping into the trenches. There was no rainfall, so this had to be moving groundwater," he said.

The team scheduled a meeting with then-TCEQ deputy director Dan Eden to share their concerns. "We told him that the site was fatally flawed. … I remember one [team] member telling Eden that if one were to stand on the floor of the proposed facility, a ‘wall of water would come toward you from three directions.’ " Eden was told that because groundwater would very likely intrude into the disposal sites, there was an increased risk that the public would be exposed to radioactive material in their drinking and agricultural water."

The team was met with "dead silence," Lewis said.

At the conclusion of the meeting, Lewis heard Eden tell the agency’s general counsel that TCEQ "had to find a way to issue this license. … I was stunned, as we had just spent an hour explaining why this site would not work."

After the meeting, Lewis and his team members prepared and signed the memo to Eden and Susan Jablonski, director of TCEQ’s radioactive materials division, explaining why the site was highly unsuitable for a radioactive waste dump. Shortly after that, Lewis and the team members were informed by Eden that TCEQ’s then-Executive Director Glenn Shankle had decided to support the license application.

Eden ordered the team to begin drafting a report that would justify licensing the site as soon as possible, Lewis said. He said Eden told the team that Waste Control executives "were impatient to receive a draft license for its review."

Lewis refused and soon resigned in protest along with two other TCEQ employees. "All of our work was for nothing," Lewis said. "It was clear that we were supposed to find some way around the problems, we were to find some way to license the place that would pass the smell test. … Well, there was no way."

Later that year, Jablolnski acknowledged in memos to senior TCEQ management that "faulty site conditions exist and that they cannot be corrected through license conditions," Lewis said. Still, she supported the license.

Contacted at her Austin office, Jablonski promised to have a staff person call back to answer questions, but no one had called by press time. Eden and Shankle could not be reached for comment.

With all of the existing low-level dumps across the nation either shut down or closed to outside states’ waste, Burnam said Texas is set to become the permanent home to millions of gallons of radioactive wastes and tons of toxic nuclear debris. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that 138 million pounds of nuclear waste are piling up at power plants in 36 states along with tons of radioactive wastes from the nation’s weapons programs — all with no place to call home.

Burnam, a Fort Worth Democrat, filed a bill last year that would have given the legislature — rather than the waste commission — the power to determine which states can export their nuclear leftovers to Texas, but the bill failed. He said the legislature could still intervene after it convenes in January, but he thinks that’s highly unlikely.

Hadden also thinks it’s possible that radioactive waste from other countries will end up in West Texas, although the dump’s license doesn’t allow it. "It will be very simple for foreign waste to come into this country, be repackaged at a Tennessee reprocessing plant, re-labeled, and sent to West Texas," she said.

After TCEQ approved the West Texas dump’s license, the waste compact commission was created to oversee it — and given the authority to make the rule changes.

Two of the eight waste compact commission members have expressed skepticism about the proposed rule change, but they don’t expect to prevail.

The waste commission set the required 30-day comment period, which ends in just a few days, on Dec. 26. Commissioners Bob Gregory and Bob Wilson expressed concerns about the proposed rule change and asked for a longer comment period but were outvoted.

The timing of the comment period is another thing that angers Hadden. "This is typical of the way things operate in Austin, setting this 30-day comment period during the holidays, when folks are very busy, and few people are paying attention to an obscure rule change by an agency that few have even heard of," she said.

Nonetheless, at a recent meeting of the waste commission in Austin, more than two dozen people showed up to protest the rule change, Hadden said. "Only about four came in support, and they were all either representatives of waste generators or Simmons’ lobbyists."

The Sierra Club has filed two lawsuits in Travis County opposing the licenses granted to Simmons’ company. One suit has been heard, and the group is waiting for a judge’s ruling. The second has yet to go to trial, a Sierra Club official said.

Simmons, whose companies are worth around $5 billion according to Forbes magazine, is a heavy-hitter in GOP campaign circles, contributing more than $3.5 million to Republicans since 2000, according to campaign finance reports. Texans for Public Justice reports that those contributions have included more than $1.1 million for Perry since 2006, including half a million dollars in just the past four months.

Additionally, two of Simmons’ lobbyists are former heads of state agencies long involved in the effort to find a low-level waste repository in the state — Rick Jacobi of Austin, who once headed the now-defunct Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Authority, and Shankle, the former executive director of TCEQ who approved the low-level licensing of Simmons’ dump before he quit to join Simmons’ team.

If the dump is indeed allowed to accept waste from all over the country, Simmons stands to make millions of dollars during the next 15 years in which the license runs. Then he could walk away, and control and maintenance of the dump would revert to the state — for thousands of years. "Liability for any nuclear accidents or radiation leaks into the environment would be borne by the state’s taxpayers," Burnam pointed out.

Lewis said that regulators and Simmons’ company officials can talk all they want about ways to mitigate problems at the site or limit damage to the environment. But what they can’t change, he said, is the basic geology.

"Other defects with the application could have been addressed through special license conditions, but the geology of the site cannot be altered. It is incompatible with protecting the environment from radiation exposure," he said. "We communicated this very clearly to TCEQ management.

"I spent four years on this [application review] and a year in Vietnam," Lewis said. "Believe me, it was worse than Vietnam."

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Controversial rules for Texas landfill could impact decommissioning of Vermont Yankee

Controversial rules for Texas landfill could impact decommissioning of Vermont Yankee

December 1, 2010

By Anne Galloway

VTDigger.org

New rules under consideration by a Texas commission could hamper the decommissioning of the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Plant in the near future, according to experts and activists who oppose the change.

They say the proposal, which would allow a Texas landfill to accept additional waste from out-of-state entities, including nuclear power companies like Entergy Corp., could give away space that is allotted for anticipated radioactive material from Vermont Yankee.

Texas formed a compact with Vermont in 1998 to establish a permanent repository for low-level radioactive waste generated by nuclear power plants and medical and research facilities in Vermont and Texas. The compact was set up for the two states’ exclusive use. (Maine was originally a part of the agreement but dropped out). In 2009, Waste Control Specialists received a license to open a radioactive waste landfill in West Texas for the compact that is now under construction.

Two weeks ago, members of the Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission, including two Douglas administration officials representing Vermont, gave preliminary approval to procedures that would allow the commission to accept applications for permits from entities in other states to dump waste at the site.

Critics say the new rules could transform the landfill into a national repository for low-level nuclear waste and that it could fill up quickly because demand for landfill space is high. Thirty-six states are not currently part of a radioactive waste disposal compact. If the Texas Commission approves the proposed procedures after a 30-day public comment period that ends Dec. 26, the West Texas facility would be the only site of its type licensed to accept waste from anywhere in the country, according to the Nuclear Information and Resource Service, an anti-nuclear group based in Maryland.

Members of the Texas Commission who support the proposals, including Uldis Vanags, the state nuclear engineer for the Vermont Department of Public Service, say they are looking out for Vermont’s interests and that opening the site to "imported" waste from "noncompact" entities will help to pay for the construction of the high-tech facility, which is slated to open at the end of 2011. Otherwise, they say, waste disposal costs for the two compact members, Texas and Vermont, would be prohibitively expensive.

"We will not give up our capacity that we need to fulfill the decommissioning of Vermont Yankee," Vanags said. "The only way (we) would consider importation is if there is surplus capacity."

Vanags said the new rule won’t have an impact on decommissioning Vermont Yankee.

Vanags, the state nuclear engineer, and Steven Wark, director of consumer affairs and public information for the Vermont Department of Public Service – both voted on Nov. 13 to support the rules, which will enable other states to apply for access to the landfill. Vanags and Wark, the only two Vermont representatives on the commission, were among the five commissioners who approved the change; two Texas members dissented.

Several Texas Compact commissioners who cast dissenting votes on the rule have questioned whether "imports" will use up capacity at the facility before Vermont has a chance to move radioactive materials from the decommissioned Vermont Yankee plant to Texas.

The proposed rules, which were promulgated in the Texas Register on Nov. 26, are now subject to a 30-day public comment period, which ends Dec. 27.

The commission is expected to make a final decision soon after the public comment period – before the new Vermont governor, Peter Shumlin, is installed and Vermont lawmakers convene for the 2011 legislative session.

Shumlin, a Democrat, and leaders of his party in the Statehouse, have been critical of Entergy Corp.’s handling of maintenance problems at the nuclear power plant in Vernon, including a transformer fire, the collapse of a cooling tower and radioactive leaks, none of which affected public safety, according to the company and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Last year, Gov.-elect Shumlin led the charge, as president pro tem of the Vermont Senate, to nix Entergy’s relicensure effort.

Storage in Vermont, or Texas?

Vermont Yankee is licensed to operate until March 2012. Unless the license is extended, which would appear politically untenable given the Vermont Senate’s decision last year to block Entergy’s bid to relicense the 38-year-old plant for 20 years, the plant will be shut down next year, preparing the way for decommissioning.

At that point, where and how the radioactive waste is stored will become a crucial issue.

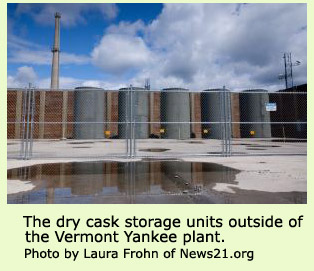

Entergy Corp. has proposed keeping the materials on the Vernon site in a system called SAFSTOR for a period of six decades.

Another alternative would be a more accelerated decommissioning process, in which the waste would be sent to the West Texas landfill overseen by the commission and operated by a Dallas-based private company, Waste Control Specialists, according to Arnie Gundersen, a nuclear engineer who is a legislative consultant via Fairewinds Associates, Inc., to the Vermont Legislature’s Joint Fiscal Committee.

The compact legally entitles Vermont under a 15-year license to 20 percent, or 462,000 cubic feet, of the 2.3 million cubic feet at the nuclear waste dump. Under the proposal, however, space could be at a premium at the waste facility if "noncompact" entities are allowed to apply for permits to deposit radioactive materials at the site in Andrews County, Texas, according to Bob Gregory, a member of the commission from Texas.

Requests for waste "importation" would be vetted on a case-by-case basis, according to the published rules.

Waste Control Specialists facility in Texas for radioactive canisters, WCS image

In 2009, the Compact Commission determined that Vermont and Texas together need a total of 6 million cubic square feet of capacity for the amount of radioactive waste generated by both states.

In 2009, the Compact Commission determined that Vermont and Texas together need a total of 6 million cubic square feet of capacity for the amount of radioactive waste generated by both states.

Gregory, one of the dissenting members, said the commission doesn’t have the staff capacity or financial resources to evaluate applications. (The annual budget of $125,000 covers travel and meeting expenses.) In addition, the subjective nature of the proposed permitting process, he said, could leave the commission vulnerable to lawsuits.

He doesn’t know how the commission will defend itself from legal challenges if the commission says no to one entity and yes to another.

"Waste control specialists, Entergy, Santa Claus – anyone can sue us for not allowing radioactive waste to come in," Gregory said. "What are we going to say if we can’t defend ourselves?"

Entergy, according to a Texas official, would have much to gain if the new landfill rules go through. The Louisiana-based corporation needs a place to put the waste from its fleet of 10 plants around the country. "Opening the Texas facility would allow them to take it from those other plants," Gregory said.

A giveaway?

Gundersen, a consultant for the Legislature, suggested that the Douglas administration supports Entergy’s proposal to put Vermont Yankee in SAFSTOR for 60 years, while the company waits for the decommissioning fund to grow enough to cover the cost of moving the material offsite.

David Coriell, the spokesman for Douglas, wrote in an e-mail that the governor "has said, on many occasions, he believes 60 years is too long."

SAFSTOR, in Gundersen’s view, is not necessary. He said Vermont Yankee could be decommissioned in 10 years, but that scenario is contingent on access to landfill capacity in Texas. There is just enough cubic square footage on the site to accommodate the radioactive waste from the plant.

"There’s a limited amount of land (for radioactive waste disposal) in Texas, and the state is giving away Vermont’s land to 35 other states, which will make it impossible to decommission Vermont Yankee," Gundersen said.

In June 2009, Vanags testified to the Vermont Public Service Board that decommissioning Vermont Yankee would cost less than the $568 million spent on Maine Yankee, even though projections that include the SAFSTOR option have been higher. Vermont Public Radio reported in 2007 that decommissioning Vermont Yankee could cost as much as $1.7 billion. In September of this year, the decommissioning fund was at about $443 million. Entergy is responsible for making sure there is adequate money available for decommissioning.

Gundersen said Vanags’ testimony was based on the assumption that the radioactive waste would be shipped to Texas.

"If Vanags’ testimony under oath is correct, we could complete decommissioning by 2020, (but) he’s giving away the land to which you need to ship it," Gundersen said. "If you give away the land, you force SAFSTOR to occur. With no place to send it, we’re sort of constipated."

Vanags, who voted to publish the rules that will allow other states to apply for access to the landfill, said: "There absolutely will be enough space."

"We will not give up our capacity that we need to fulfill the decommissioning of Vermont Yankee," he said.

In audio testimony, Vanags and Wark voted against amendments to the proposed rules that would have given Compact members first dibs to the landfill and also that would have delayed action and allowed the Texas and Vermont legislatures an opportunity to weigh in on the matter.

"We’re actually under the closing phases of the Douglas administration," Gundersen said. "We’re getting to the point where we, the state of Vermont’s administrative agencies, are actually assisting Entergy, as opposed to looking out for the best interests of the state."

Gregory, a Texas commission member who opposed the adoption of the new rules, said he doesn’t understand why the rule has to be adopted by early January. He suspects the timing has something to do with a changing of the political guard in the Vermont governor’s office.

"What on Earth is the rush?" Gregory said. "It’s rushing to beat a date for when the new governor comes to town. If the commissioners change, then the vote would be 4-4; now it’s 6-2."

The terms for the commissioners from Vermont – Vanags, Wark and their alternate Sarah Hoffman – expire Feb. 28, 2010. Gov.-elect Shumlin, in the interim, will likely appoint a new commissioner for the Department of Public Service, who could in turn name new "exempt" employees, or appointed officials, who would take the place of the three who are now on the commission.

Tom Smith, of Public Citizen, an advocacy group that opposes the landfill, said the commission wants to get the rule rammed through before the Texas and Vermont legislatures have a chance to take action to block it.

"They’re afraid the new governor of Vermont might appoint commissioners that might stand up for the state, as opposed to going along with what the nuclear industry wants," Smith said.

John C. White, vice chair of the commission and a radiation safety officer for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, says nothing of the sort is going on.

"We’ve been talking about this for 16 months," White said of the rule. "We can amend the rule if necessary … I don’t see your new governor as part of this."

The rationale for taking all comers

The facility, which is designed to take radioactive materials such as contaminated clothing, glass, metal, reactor components and sludge, needs a certain amount of waste to cover the fixed costs associated with construction.

White, speaking as commission vice chair, said allowing material from other states into the landfill would lower the operating costs for the compact members tenfold.

Vanags said opening up the site to more entities will keep disposal fees at the site reasonable for Texas and Vermont. The commission hasn’t set fees for "imports," but so far it hasn’t imposed up-front contributions from noncompact waste generators. Vermont will pay $25 million to support construction of the site this year.

"The way to reduce cost per cubic foot is to increase your capacity," Vanags said in contending the only way the commission would consider "imports" would be if there is surplus capacity.

Vanags said before the commission would accept applications, it would conduct an updated study to determine how much capacity would be needed by the two compact states.

"We recognize as a commission we have to have a process (for dealing with requests)," Vanags said. "We’re not opposed to importation. We’re open to it, but as long as our capacity is protected. The facility in the future may be expanded, and they may amend their license. In future, there may be surplus capacity."

White supports expanding the site to accommodate more waste. The limitations now placed on the landfill are under the terms of the current license issued by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, White said. The site itself, he believes, could be expanded.

In the meantime, demand is high, White said. Medical waste vendors are already coming in to the state of Texas in anticipation of the facility opening a year from now, he said. Hospitals are having a difficult time disposing of waste used in research and in the treatment of cancer, he said.

"So many people say you’re opening the door," White said. "The door is already open. Waste is already coming in to Texas, and we don’t have control over where the waste is stored. We don’t have procedures to say you can’t bring it in."

CLARIFICATION: The following sentence was added to the story, 11:20 a.m. Dec. 2, 2010: David Coriell, the spokesman for Douglas, wrote in an e-mail that the governor "has said, on many occasions, he believes 60 years is too long."

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Shumlin Says Proposal Could Squeeze VT Out Of Nuclear Waste Dump

December 14, 2010

John Dillon – Montpelier, VT

Vermont Public Radio -NPR

(Host) The dry plains of west Texas are supposed to be the final resting place for tons of low-level nuclear trash. Vermont and Texas have exclusive rights to the proposed waste site under an agreement reached 16 years ago.

But the commission overseeing the dump wants to open up the site to 36 other states.

That possibility worries Governor-elect Peter Shumlin. As VPR’s John Dillon reports, Shumlin says Vermont could get squeezed out if other states have access to the nuclear waste site.

(Dillon) Back in the 1990s Vermont and Texas planned ahead and signed an interstate compact for low level nuclear waste. The deal says Texas will host the dump, and Vermont is supposed to get 20 percent of the space.

But just days after the November election, the commission overseeing the project voted to propose a new rule that would open up the site to other states. It was a controversial decision, with some on the panel warning that the vote was being rushed.

(Gregory) "I am convinced this is too much, too soon, too fast."

(Dillon) That’s Texas commissioner Bob Gregory speaking out against the proposal at meeting in Midland, Texas, last month.

Gregory told the two Vermont commissioners that Vermont could lose its space in the dump if it was made available to nuclear plants in other states.

(Gregory) "I want you all to know that these things are being discussed and they’re being said, and one day ifVermont comes up and says: ‘Where’s our volume, where’s our capacity?’ And it is no more, that at least it was discussed."

(Dillon) Steve Wark was also in Midland that day. Wark is deputy public service commissioner and is one of two Vermonters who serve on the eight-member Low Level Waste Commission.

Wark and the other Vermonter on the panel – state nuclear engineer Uldis Vanags – were the swing votes in favor of the proposal to allow waste from other states. Wark told the November meeting that he’s aware of the implications for Vermont.

(Wark) "We definitely appreciate raising these issues for Vermont. We see them as important to Vermont. We wanted to protect our space. However, we do believe the rule meets all of Vermont’s needs."

(Dillon) But Governor-elect Peter Shumlin is not convinced. Shumlin says Vermont will need the Texas dump when Vermont Yankee is decommissioned.

(Shumlin) "There’s going to be a race for space, and the first in wins."

(Dillon) And Shumlin questions the timing of the vote – which came two months before he gets to replace the Douglas administration appointees on the panel.

(Shumlin) "My view is that the folks who are voting and scrambling before I become governor, frankly, to ensure that all the other states get access to our waste site are not thinking of Vermonters."

(Dillon) But Wark said in an interview that Vermont has a solid guarantee to the space under the new rule.

(Wark) "Our space is protected first, regardless of what else comes in from any other state."

(Dillon) Wark said allowing other nuclear plants to use the site will lower the cost overall. He said the proposal was under discussion for months, and that the vote was not rushed through before the change in administrations.

But a final vote on the rule could take place before Shumlin takes office on January 6.

Shumlin wants a delay and so do leading Democratic lawmakers.

For VPR News, I’m John Dillon in Montpelier.

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Don’t make Texas the nation’s radioactive waste dump

Friday, December 10, 2010

By Karen Hadden/Guest Column

San Antonio Express News

Texas is at risk of becoming the nation’s radioactive waste dumping ground. The Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is pushing forward a rule that essentially invites 36 or more states to dump radioactive waste in Texas. It would go to the Waste Control Specialists’ site in Andrews County in West Texas.

The commission should instead limit the site to waste from the Compact states — Texas and Vermont. Financial and safety risks are being ignored in the rush to approve the rule, which has no limits on volume or curies of radiation. Texas has liability for imported radioactive waste and 15 state legislators have asked for time to review the increased financial and environmental risks, but the Compact Commission is trying to vote on the import rule right away.

Radioactive waste could travel by rail and on major highways throughout our state and no one has analyzed whether emergency responders throughout Texas are equipped to deal with accidents involving radioactive waste.

Everything but the fuel rods from nuclear reactors can go to a "low-level" radioactive waste dump, including nuclear reactor vessels, poison curtains that absorb core radioactivity, and radioactive sludges and resins. No radioactive element is excluded. Exposure to radiation can lead to cancer and birth defects and the materials remain hazardous for hundreds to millions of years.

Staff at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality recommended denying the Compact site license. They said "groundwater is likely to intrude into the proposed disposal units and contact the waste from either or both of two water tables near the proposed facility."

The Compact site is already pressed for space. It’s licensed for 2.3 million cubic feet of waste, but Texas and Vermont need three times this space to dispose of five nuclear reactors when they’re decommissioned. Why bring in waste from around the country and force expansion of the site?

Is Waste Control Specialists trying to create a "volume discount" rate for dumping radioactive waste on Texas? A private company headed by Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons would profit while Texas’ taxpayers would bear increased financial and safety risks. Existing U.S. radioactive waste dumps have leaked and clean up will cost billions of dollars. Why increase the risks of contaminating Texas’ soil and water by bringing in waste from around the country?

It’s not too late. Other compacts have excluded "out-of compact" waste and Texas could close the gate too. Citizens can urge elected officials to insist on limiting the radioactive waste coming to Texas. Comments on the Compact Commission Import rule can be sent to www.tllrwdcc.org/rule675.html until Dec. 26. The import rule vote should be halted until waste limits are assured and the legislature has a chance to analyze financial, health and safety risks to Texans. If you don’t want Texas to become the nation’s radioactive waste dump, the time to speak up is now.

Karen Hadden is executive director of the SEED Coalition.

Nuclear ‘Renaissance’ Is Short on Largess

December 7,2010

By MATTHEW L. WALD

New York Times

The federal aid now in place for new nuclear plants is far from sufficient for the so-called "nuclear renaissance" that backers are seeking, a panel made up of members of Congress, high-ranking federal officials and leaders of major nuclear companies agreed on Tuesday.

Ground has been broken on only two new nuclear plants with a total of four reactors, and some companies have withdrawn their applications for licenses to build. "We can’t make the numbers work," said Chip Pardee, chief nuclear officer of Exelon, the nation’s largest operator of civilian nuclear reactors, who sat on a panel of 25 at a conference organized by the Idaho National Laboratory of the Energy Department and a private group called the Third Way.

Read more at the New York Times web site….

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.