Author Archive

Judge halts radioactive dump plan for now

Dec. 30, 2010

By JAY ROOT

ASSOCIATED PRESS/Houston Chronicle

AUSTIN — A Texas judge ordered a temporary halt Thursday to a proposal that could allow three dozen states to dump their radioactive waste in far West Texas, a ruling that sided with environmentalists and caught the state attorney general’s office off guard.

State District Judge Jon Wisser issued a temporary restraining order against the Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission, which is scheduled to vote Jan. 4 on rules that could expand how much waste could be processed at a dump in remote Andrews County.

The injunction was issued in the judge’s courtroom late Thursday morning, shortly after environmentalists filed the request, with nobody there representing the commission. A few minutes later, shocked lawyers from the Texas Attorney General’s Office – which hadn’t been officially notified of the pending court action – showed up and persuaded the judge to order a new hearing on the injunction.

The hearing is set for Monday in Austin, one day before the commission’s scheduled vote.

Environmentalists sought the ruling after accusing regulators and a politically connected company of rushing the waste expansion proposal past Texas residents who were too focused on the holidays to notice.

Waste Control Specialists, whose majority owner is Dallas billionaire and prolific political donor Harold Simmons, wants state regulators to approve its proposal to allow low-level radioactive waste at its West Texas dump site from three dozen states. As it stands, the compact site can only get waste from Texas, Vermont and the federal government.

The timing of the commission’s vote next week has its own political intrigue.

The commission has six members from Texas and two from Vermont. The incoming governor of Vermont, Democrat Peter Shumlin, has publicly criticized the proposal, but he doesn’t take office until Jan. 6. By then, the two commissioners appointed by his predecessor could vote in favor of the plan, given their past support of the rule.

In their court filings Thursday, environmentalists said many Texans wanting to comment on the proposal were blocked from doing so because the commission used a defective e-mail address and then ended its 30-day public comment period on the day after Christmas, when federal post offices were closed.

Charles Herring, an attorney for environmental group Public Citizen, said the commission violated several procedures and was trying to quickly adopt new rules in order to reward billionaire Simmons.

"They shouldn’t be able to violate seven laws just to pay a political favor to somebody, with the result being we’re going to degrade the environment and threaten the folks with radioactive waste," Herring said.

Chuck McDonald, a spokesman for Waste Control Specialist, described Thursday’s court action as a legal stunt designed to delay the vote past the swearing-in of the Vermont governor.

"It is disappointing that after two years of public input and hours of public testimony, we’ve come to this last-ditch attempt to derail what has been a very thorough and open process," McDonald said. "I think they’re merely trying to buy a couple days’ delay."

The environmentalists sued the commission Thursday to halt the vote, and acknowledged that they didn’t tell the attorney general’s office. They said the bi-state commission is not set up as a traditional Texas agency and does not get legal representation from the state.

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

A Last-Minute Choice by Texas and Vermont

December 30, 2010

By MATTHEW L. WALD

New York Times

Demonstrators marched in Montpelier last January in support of retiring the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant. Tearing down the reactor will generate substantial waste.Associated Press Demonstrators marched in Montpelier last January in support of retiring the Vermont Yankee nuclear power plant. Tearing down the reactor will generate substantial waste.

Vermont and Texas, the odd couple of nuclear waste disposal, are proceeding with a plan to allow 36 other states to use a dump site under development in west Texas, despite the misgivings of Vermont’s incoming governor, Peter Shumlin, about the move.

The issue confronts the two states because 16 years ago they formed a "compact" to establish a repository for low-level radioactive waste.

Under federal law, states in a compact can limit a dump site to their own use. But with a dump now being developed in Andrews, Tex., near the New Mexico state line, a commission made up of representatives of the two states has proposed letting in waste from other states.

A public comment period ended on Dec. 26. The commission has scheduled a vote for Jan. 4, two days before Mr. Shumlin is scheduled to take office in Montpelier.

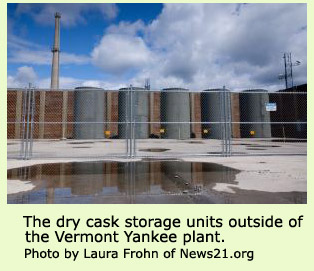

Mr. Shumlin opposes the policy; he has expressed worry that if waste from other states is allowed in, there might not be enough space left for Vermont, especially since he is calling for the shutdown of Vermont’s only nuclear reactor, Vermont Yankee. Tearing it down will generate substantial nuclear waste that will require burial somewhere.

Opponents of the plan say that 5,000 comments have been filed, most of which presumably oppose the move. Proponents argue that the volume of waste produced by Vermont and Texas is so small that costs per cubic foot of waste will be too high. They can lower the cost, they say, by inviting other waste generators, mostly power plants but also hospitals and laboratories, to bury wastes there. Outsiders would pay higher rates.

The proponents add that there is plenty of space for all of Vermont’s waste, even rubble from the reactor.

In Montpelier, David O’Brien, the public service commissioner, who will leave office as Mr. Shumlin is sworn in, said in a telephone interview: "We’re going to take the vote we’re going to take. It’s a logical progression of what we’ve been doing, and we’re not going to reverse field here."

But, he said, if Mr. Shumlin appointed new members to the commission, they could probably reverse the policy later, since many subsequent votes would be needed.

Elizabeth H. Miller, who has been designated by Mr. Shumlin to succeed Mr. O’Brien at the Public Service Commission, said that the governor elect had asked that Vermont’s two delegates on the interstate compact commission sit out the Jan. 4 meeting, but that they would not do so. She agreed with Mr. O’Brien, though, that there would be votes in the future before waste could be imported.

"The incoming administration is going to be very active" on the issue, Ms. Miller said.

Nuclear Waste From as Many as 36 States May Rumble Down Texas Highways if Texas Nuclear Waste Importation Plan Is Approved

Texans Have Until Sunday to Speak Against Radioactive Waste Rolling Along Highways and Rails

For Immediate Release:

Dec. 23, 2010

Contact:

Tom "Smitty" Smith (512) 477-1155

Trevor Lovell (512) 470-6572

Karen Hadden 512-797-8451

Download this release in pdf format for printing.

AUSTIN – Standing in front of a trailer full of black waste barrels representing radioactive waste, Public Citizen and the Sustainable Energy and Economic Development (SEED) Coalition today detailed a slew of problems associated with a plan to ship radioactive waste from 36 states into Texas.

"Texas radioactive waste commissioners are considering new rules that could allow Texas to become the nation’s radioactive waste dumping ground. The volume of waste transported, imported and stored could go up as much as 19 times," said Tom "Smitty" Smith, director of Public Citizen’s Texas office. "Our state law was designed to protect us from taking waste from many states. However, if these rules are changed, generators from all over the country can petition to send their waste to Texas if the commissioners approve the importation. Texans could get stuck paying billions to clean up the mess left behind."

The event was designed to raise awareness about the dangers of hauling so much radioactive waste through Texas towns by truck and rail. While routes are not yet designated, potential routes would take waste from the Gulf Coast area on Interstate 10 through Houston and San Antonio; waste from southern states would be trucked on I-20 and I-30 though Dallas and Forth Worth; Midwestern and Northeastern waste would be driven on I-40 and I-27 though Lubbock and Amarillo; and waste from Western states would be driven though the cities of El Paso and Odessa taking I-10 and I-20, according to Martin Resnikoff of Radioactive Waste Management Associates.

On Aug. 24, 2001, it was revealed that a 22-ton shipment of waste from an Illinois gaseous diffusion plant headed for Andrews, Texas, was lost for nearly a month. It was later found dumped on a North Texas cattle ranch near Oklahoma, piled on plastic and covered with dirt.

"Truck crashes occur all the time on our highways," Smith said. "This plan would dramatically increase the amount of radioactive waste traveling through our communities. We believe that if people know what is at stake, they will contact state officials and demand that the compact commission drop the proposal."

Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) rules provide that class "A" wastes can be shipped in so-called "strong tight containers," barrels that do not have to pass any integrity test. About 10 percent of these containers that have been involved in accidents have failed. Of those, about 90 percent have released their contents, according to the NRC.

Under a 2003 agreement, a dump in Andrews County was designated to take radioactive waste from just Texas and Vermont. Now, the Texas Low Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is proposing to allow the importation of low-level radioactive waste from 36 states that don’t have anywhere to ship it.

The proposed dump would be operated by Waste Control Specialists (WCS), which is owned by Simmons, a politically powerful Republican who helped bankroll the Swift Boat attacks on Sen. John Kerry and who, according to Texans for Public Justice, has given Texas Gov. Rick Perry $1.12 million over the past decade, including $500,000 in 2010, making Simmons the No. 2 all-time individual donor to the governor.

The commission proposed rules earlier this year for such an expansion but withdrew them after receiving more than 3,000 comments from the public, most of them adamantly opposed to importation. On Nov. 3, the morning after the elections, the commission announced the rules would be re-posted with only minor changes. Citizens have until Sunday to submit comments.

"This looks like a Christmas present for a major donor," said Karen Hadden, director of the SEED Coalition. "Would Waste Control Specialists be able to expand so greatly if its owner wasn’t so politically connected? We suspect not."

"This is a blatant attempt to get these rules through while the public is busy with the holidays," Hadden added. "The commission should postpone these rules until both the Texas and Vermont legislatures – and the incoming Vermont governor – can consider the matter. Building a national nuclear waste dump in Texas violates the intent of the original Texas-Vermont agreement, which would limit the waste and raises a host of serious safety concerns that lawmakers need to consider."

A primary concern for the Texas Legislature would be the state’s liability for the waste. Under state law, once the waste is accepted for disposal, the taxpayers – not WCS – are liable for any spills, seepage into the groundwater or other contamination. This could easily result in millions or even billions of dollars in liability for Texans – far more than the $136 million dollar bond posted by WCS for such problems. For example, the Western New York Nuclear Service Center in West Valley, N.Y., could cost $9.9 billion or more to clean up, according to an analysis by Synapse Energy.

The staff who reviewed the permit at the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) unanimously recommended against granting a license for a low-level radioactive waste dump. In an interoffice memo, TCEQ technical staff said that it was "highly likely" that radioactive waste would leak into groundwater. Several quit in protest when their recommendations went unheeded by then-Executive Director Glenn Shankle and the facility was licensed anyway. Shankle went on to work for Simmons as a lobbyist, representing WCS just six months after leaving the TCEQ.

Risks of groundwater contamination are a significant concern. Maps have been in flux while a hot debate centers on whether the WCS site is connected to the Ogallala, a huge aquifer that provides drinking water for nearly two million people and extends beneath eight states, also supplying water for more than a quarter of the country’s irrigated land.

"People have to understand that this is their last shot to block a national radioactive waste dump from being built in Texas, with all the dangers that come with that," Smith said. "We urge Texans to send comments and ask the commission to push the pause button on this proposal until such time as the legislature has a chance to look at the risks from an accident or from a leak. This proposal is being railroaded through the process before the fiscally conservative Texas Legislature recognizes what a giveaway this is."

Instructions and suggestions for comments are available at http://www.TexasNuclearSafety.org .

All photos courtesy of Andy Wilson.

###

Public Citizen is a national, nonprofit consumer advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C., with an office in Austin, Texas.

The Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition is working for Clean Air and Clean Energy in Texas

High-Level Worries

Environmentalists are still fighting a dump that could bring in much more nuclear waste than originally thought.

Wednesday, 22 December 2010

BETTY BRINK

Fort Worth Weekly

By the fall of 2011, if the courts or legislators don’t act to stop it, Texas could become the "nuclear waste dump for the country if not the world," State Rep. Lon Burnam says. And he and a coalition of environmental groups are leading a last-ditch effort to stop the waste trains and trucks from rolling through Fort Worth and other parts of Texas to the site on the New Mexico border — owned by a major contributor to Gov. Rick Perry — that sits atop part of the nation’s largest aquifer.

The 1,338-acre site was licensed in 2009 with authority to accept nuclear waste from only two states, Texas and Vermont, plus "byproducts" from certain closed federal sites such as uranium processing plants. Now, however, after heavy lobbying from the dump’s Dallas billionaire owner Harold Simmons, the state’s Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is set to vote in early January on a rule that would allow the dump to throw open its gates to nuclear waste from every state.

The 1,338-acre site was licensed in 2009 with authority to accept nuclear waste from only two states, Texas and Vermont, plus "byproducts" from certain closed federal sites such as uranium processing plants. Now, however, after heavy lobbying from the dump’s Dallas billionaire owner Harold Simmons, the state’s Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission is set to vote in early January on a rule that would allow the dump to throw open its gates to nuclear waste from every state.

The original license was approved by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality only after years of geological study, environmental impact statements, and public hearings. But the new rule, vastly increasing the volume of dangerous wastes moving to the site, could be approved by the waste disposal commission without any public hearings, further studies, or input beyond a 30-day comment period, which ends this week.

Karen Hadden, head of the nonprofit Sustainable Energy and Economic Development Coalition based in Austin, is pushing her member groups to demand that TCEQ require a full environmental impact study to be undertaken before any waste crosses the Texas border. "This will have a tremendous environmental impact on West Texas and the aquifers there, and it makes no sense not to do [the environmental studies]," she said.

The granting of the original license to Waste Control Specialists, owned by Simmons, was hugely controversial. TCEQ approved the license despite vigorous opposition from the state’s own scientific experts, who found that the site was geologically unsound and would not be stable enough to protect humans and the environment, especially the Ogallala aquifer, during the hundreds of thousands of years that the wastes will be dangerous. Three TCEQ employees resigned in protest when the agency overruled their recommendation that the license be denied.

In recent months, however, the full story of that licensing process has been revealed by one of the three TCEQ employees who quit. Glenn Lewis, the technical editor of the TCEQ team at that time, is now one of the agency’s most vocal critics.

The potential for contamination of the Ogallala is real, said Lewis, and that fact was explained in detail to top TCEQ administrators and commissioners at the time.

After four years of study of the Waste Control application, the TCEQ technical team reported in a memo that because groundwater from two nearby water tables would "intrude into the … disposal units and contact the waste," the site "is not suitable for near-surface disposal of radioactive waste."

Although Waste Control Specialists claimed initially that there was at least 120 feet of "impenetrable red bed clay between the site and the nearest groundwater, the team found groundwater within 12 feet of the bottom of the storage facility," Lewis said, "too close for a facility that must contain waste for more than 50,000 years.

"It is a tenet of federal and state law that intrusions of water into buried radioactive waste must be avoided," he said. "This site does not in any way, shape, or form meet those standards." He pointed out that "low-level" does not mean "low-radiation." It can be "the most dangerous kinds of waste" from nuclear power plants and nuclear weapons programs, he said.

The West Texas site is a "nest of related holes in the ground [for burial of all of the different types of waste sent there]," he said, "and there was always standing water in the pits, seeping into the trenches. There was no rainfall, so this had to be moving groundwater," he said.

The team scheduled a meeting with then-TCEQ deputy director Dan Eden to share their concerns. "We told him that the site was fatally flawed. … I remember one [team] member telling Eden that if one were to stand on the floor of the proposed facility, a ‘wall of water would come toward you from three directions.’ " Eden was told that because groundwater would very likely intrude into the disposal sites, there was an increased risk that the public would be exposed to radioactive material in their drinking and agricultural water."

The team was met with "dead silence," Lewis said.

At the conclusion of the meeting, Lewis heard Eden tell the agency’s general counsel that TCEQ "had to find a way to issue this license. … I was stunned, as we had just spent an hour explaining why this site would not work."

After the meeting, Lewis and his team members prepared and signed the memo to Eden and Susan Jablonski, director of TCEQ’s radioactive materials division, explaining why the site was highly unsuitable for a radioactive waste dump. Shortly after that, Lewis and the team members were informed by Eden that TCEQ’s then-Executive Director Glenn Shankle had decided to support the license application.

Eden ordered the team to begin drafting a report that would justify licensing the site as soon as possible, Lewis said. He said Eden told the team that Waste Control executives "were impatient to receive a draft license for its review."

Lewis refused and soon resigned in protest along with two other TCEQ employees. "All of our work was for nothing," Lewis said. "It was clear that we were supposed to find some way around the problems, we were to find some way to license the place that would pass the smell test. … Well, there was no way."

Later that year, Jablolnski acknowledged in memos to senior TCEQ management that "faulty site conditions exist and that they cannot be corrected through license conditions," Lewis said. Still, she supported the license.

Contacted at her Austin office, Jablonski promised to have a staff person call back to answer questions, but no one had called by press time. Eden and Shankle could not be reached for comment.

With all of the existing low-level dumps across the nation either shut down or closed to outside states’ waste, Burnam said Texas is set to become the permanent home to millions of gallons of radioactive wastes and tons of toxic nuclear debris. The U.S. Department of Energy estimates that 138 million pounds of nuclear waste are piling up at power plants in 36 states along with tons of radioactive wastes from the nation’s weapons programs — all with no place to call home.

Burnam, a Fort Worth Democrat, filed a bill last year that would have given the legislature — rather than the waste commission — the power to determine which states can export their nuclear leftovers to Texas, but the bill failed. He said the legislature could still intervene after it convenes in January, but he thinks that’s highly unlikely.

Hadden also thinks it’s possible that radioactive waste from other countries will end up in West Texas, although the dump’s license doesn’t allow it. "It will be very simple for foreign waste to come into this country, be repackaged at a Tennessee reprocessing plant, re-labeled, and sent to West Texas," she said.

After TCEQ approved the West Texas dump’s license, the waste compact commission was created to oversee it — and given the authority to make the rule changes.

Two of the eight waste compact commission members have expressed skepticism about the proposed rule change, but they don’t expect to prevail.

The waste commission set the required 30-day comment period, which ends in just a few days, on Dec. 26. Commissioners Bob Gregory and Bob Wilson expressed concerns about the proposed rule change and asked for a longer comment period but were outvoted.

The timing of the comment period is another thing that angers Hadden. "This is typical of the way things operate in Austin, setting this 30-day comment period during the holidays, when folks are very busy, and few people are paying attention to an obscure rule change by an agency that few have even heard of," she said.

Nonetheless, at a recent meeting of the waste commission in Austin, more than two dozen people showed up to protest the rule change, Hadden said. "Only about four came in support, and they were all either representatives of waste generators or Simmons’ lobbyists."

The Sierra Club has filed two lawsuits in Travis County opposing the licenses granted to Simmons’ company. One suit has been heard, and the group is waiting for a judge’s ruling. The second has yet to go to trial, a Sierra Club official said.

Simmons, whose companies are worth around $5 billion according to Forbes magazine, is a heavy-hitter in GOP campaign circles, contributing more than $3.5 million to Republicans since 2000, according to campaign finance reports. Texans for Public Justice reports that those contributions have included more than $1.1 million for Perry since 2006, including half a million dollars in just the past four months.

Additionally, two of Simmons’ lobbyists are former heads of state agencies long involved in the effort to find a low-level waste repository in the state — Rick Jacobi of Austin, who once headed the now-defunct Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Authority, and Shankle, the former executive director of TCEQ who approved the low-level licensing of Simmons’ dump before he quit to join Simmons’ team.

If the dump is indeed allowed to accept waste from all over the country, Simmons stands to make millions of dollars during the next 15 years in which the license runs. Then he could walk away, and control and maintenance of the dump would revert to the state — for thousands of years. "Liability for any nuclear accidents or radiation leaks into the environment would be borne by the state’s taxpayers," Burnam pointed out.

Lewis said that regulators and Simmons’ company officials can talk all they want about ways to mitigate problems at the site or limit damage to the environment. But what they can’t change, he said, is the basic geology.

"Other defects with the application could have been addressed through special license conditions, but the geology of the site cannot be altered. It is incompatible with protecting the environment from radiation exposure," he said. "We communicated this very clearly to TCEQ management.

"I spent four years on this [application review] and a year in Vietnam," Lewis said. "Believe me, it was worse than Vietnam."

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.

Controversial rules for Texas landfill could impact decommissioning of Vermont Yankee

Controversial rules for Texas landfill could impact decommissioning of Vermont Yankee

December 1, 2010

By Anne Galloway

VTDigger.org

New rules under consideration by a Texas commission could hamper the decommissioning of the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Plant in the near future, according to experts and activists who oppose the change.

They say the proposal, which would allow a Texas landfill to accept additional waste from out-of-state entities, including nuclear power companies like Entergy Corp., could give away space that is allotted for anticipated radioactive material from Vermont Yankee.

Texas formed a compact with Vermont in 1998 to establish a permanent repository for low-level radioactive waste generated by nuclear power plants and medical and research facilities in Vermont and Texas. The compact was set up for the two states’ exclusive use. (Maine was originally a part of the agreement but dropped out). In 2009, Waste Control Specialists received a license to open a radioactive waste landfill in West Texas for the compact that is now under construction.

Two weeks ago, members of the Texas Low-Level Radioactive Waste Disposal Compact Commission, including two Douglas administration officials representing Vermont, gave preliminary approval to procedures that would allow the commission to accept applications for permits from entities in other states to dump waste at the site.

Critics say the new rules could transform the landfill into a national repository for low-level nuclear waste and that it could fill up quickly because demand for landfill space is high. Thirty-six states are not currently part of a radioactive waste disposal compact. If the Texas Commission approves the proposed procedures after a 30-day public comment period that ends Dec. 26, the West Texas facility would be the only site of its type licensed to accept waste from anywhere in the country, according to the Nuclear Information and Resource Service, an anti-nuclear group based in Maryland.

Members of the Texas Commission who support the proposals, including Uldis Vanags, the state nuclear engineer for the Vermont Department of Public Service, say they are looking out for Vermont’s interests and that opening the site to "imported" waste from "noncompact" entities will help to pay for the construction of the high-tech facility, which is slated to open at the end of 2011. Otherwise, they say, waste disposal costs for the two compact members, Texas and Vermont, would be prohibitively expensive.

"We will not give up our capacity that we need to fulfill the decommissioning of Vermont Yankee," Vanags said. "The only way (we) would consider importation is if there is surplus capacity."

Vanags said the new rule won’t have an impact on decommissioning Vermont Yankee.

Vanags, the state nuclear engineer, and Steven Wark, director of consumer affairs and public information for the Vermont Department of Public Service – both voted on Nov. 13 to support the rules, which will enable other states to apply for access to the landfill. Vanags and Wark, the only two Vermont representatives on the commission, were among the five commissioners who approved the change; two Texas members dissented.

Several Texas Compact commissioners who cast dissenting votes on the rule have questioned whether "imports" will use up capacity at the facility before Vermont has a chance to move radioactive materials from the decommissioned Vermont Yankee plant to Texas.

The proposed rules, which were promulgated in the Texas Register on Nov. 26, are now subject to a 30-day public comment period, which ends Dec. 27.

The commission is expected to make a final decision soon after the public comment period – before the new Vermont governor, Peter Shumlin, is installed and Vermont lawmakers convene for the 2011 legislative session.

Shumlin, a Democrat, and leaders of his party in the Statehouse, have been critical of Entergy Corp.’s handling of maintenance problems at the nuclear power plant in Vernon, including a transformer fire, the collapse of a cooling tower and radioactive leaks, none of which affected public safety, according to the company and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Last year, Gov.-elect Shumlin led the charge, as president pro tem of the Vermont Senate, to nix Entergy’s relicensure effort.

Storage in Vermont, or Texas?

Vermont Yankee is licensed to operate until March 2012. Unless the license is extended, which would appear politically untenable given the Vermont Senate’s decision last year to block Entergy’s bid to relicense the 38-year-old plant for 20 years, the plant will be shut down next year, preparing the way for decommissioning.

At that point, where and how the radioactive waste is stored will become a crucial issue.

Entergy Corp. has proposed keeping the materials on the Vernon site in a system called SAFSTOR for a period of six decades.

Another alternative would be a more accelerated decommissioning process, in which the waste would be sent to the West Texas landfill overseen by the commission and operated by a Dallas-based private company, Waste Control Specialists, according to Arnie Gundersen, a nuclear engineer who is a legislative consultant via Fairewinds Associates, Inc., to the Vermont Legislature’s Joint Fiscal Committee.

The compact legally entitles Vermont under a 15-year license to 20 percent, or 462,000 cubic feet, of the 2.3 million cubic feet at the nuclear waste dump. Under the proposal, however, space could be at a premium at the waste facility if "noncompact" entities are allowed to apply for permits to deposit radioactive materials at the site in Andrews County, Texas, according to Bob Gregory, a member of the commission from Texas.

Requests for waste "importation" would be vetted on a case-by-case basis, according to the published rules.

Waste Control Specialists facility in Texas for radioactive canisters, WCS image

In 2009, the Compact Commission determined that Vermont and Texas together need a total of 6 million cubic square feet of capacity for the amount of radioactive waste generated by both states.

In 2009, the Compact Commission determined that Vermont and Texas together need a total of 6 million cubic square feet of capacity for the amount of radioactive waste generated by both states.

Gregory, one of the dissenting members, said the commission doesn’t have the staff capacity or financial resources to evaluate applications. (The annual budget of $125,000 covers travel and meeting expenses.) In addition, the subjective nature of the proposed permitting process, he said, could leave the commission vulnerable to lawsuits.

He doesn’t know how the commission will defend itself from legal challenges if the commission says no to one entity and yes to another.

"Waste control specialists, Entergy, Santa Claus – anyone can sue us for not allowing radioactive waste to come in," Gregory said. "What are we going to say if we can’t defend ourselves?"

Entergy, according to a Texas official, would have much to gain if the new landfill rules go through. The Louisiana-based corporation needs a place to put the waste from its fleet of 10 plants around the country. "Opening the Texas facility would allow them to take it from those other plants," Gregory said.

A giveaway?

Gundersen, a consultant for the Legislature, suggested that the Douglas administration supports Entergy’s proposal to put Vermont Yankee in SAFSTOR for 60 years, while the company waits for the decommissioning fund to grow enough to cover the cost of moving the material offsite.

David Coriell, the spokesman for Douglas, wrote in an e-mail that the governor "has said, on many occasions, he believes 60 years is too long."

SAFSTOR, in Gundersen’s view, is not necessary. He said Vermont Yankee could be decommissioned in 10 years, but that scenario is contingent on access to landfill capacity in Texas. There is just enough cubic square footage on the site to accommodate the radioactive waste from the plant.

"There’s a limited amount of land (for radioactive waste disposal) in Texas, and the state is giving away Vermont’s land to 35 other states, which will make it impossible to decommission Vermont Yankee," Gundersen said.

In June 2009, Vanags testified to the Vermont Public Service Board that decommissioning Vermont Yankee would cost less than the $568 million spent on Maine Yankee, even though projections that include the SAFSTOR option have been higher. Vermont Public Radio reported in 2007 that decommissioning Vermont Yankee could cost as much as $1.7 billion. In September of this year, the decommissioning fund was at about $443 million. Entergy is responsible for making sure there is adequate money available for decommissioning.

Gundersen said Vanags’ testimony was based on the assumption that the radioactive waste would be shipped to Texas.

"If Vanags’ testimony under oath is correct, we could complete decommissioning by 2020, (but) he’s giving away the land to which you need to ship it," Gundersen said. "If you give away the land, you force SAFSTOR to occur. With no place to send it, we’re sort of constipated."

Vanags, who voted to publish the rules that will allow other states to apply for access to the landfill, said: "There absolutely will be enough space."

"We will not give up our capacity that we need to fulfill the decommissioning of Vermont Yankee," he said.

In audio testimony, Vanags and Wark voted against amendments to the proposed rules that would have given Compact members first dibs to the landfill and also that would have delayed action and allowed the Texas and Vermont legislatures an opportunity to weigh in on the matter.

"We’re actually under the closing phases of the Douglas administration," Gundersen said. "We’re getting to the point where we, the state of Vermont’s administrative agencies, are actually assisting Entergy, as opposed to looking out for the best interests of the state."

Gregory, a Texas commission member who opposed the adoption of the new rules, said he doesn’t understand why the rule has to be adopted by early January. He suspects the timing has something to do with a changing of the political guard in the Vermont governor’s office.

"What on Earth is the rush?" Gregory said. "It’s rushing to beat a date for when the new governor comes to town. If the commissioners change, then the vote would be 4-4; now it’s 6-2."

The terms for the commissioners from Vermont – Vanags, Wark and their alternate Sarah Hoffman – expire Feb. 28, 2010. Gov.-elect Shumlin, in the interim, will likely appoint a new commissioner for the Department of Public Service, who could in turn name new "exempt" employees, or appointed officials, who would take the place of the three who are now on the commission.

Tom Smith, of Public Citizen, an advocacy group that opposes the landfill, said the commission wants to get the rule rammed through before the Texas and Vermont legislatures have a chance to take action to block it.

"They’re afraid the new governor of Vermont might appoint commissioners that might stand up for the state, as opposed to going along with what the nuclear industry wants," Smith said.

John C. White, vice chair of the commission and a radiation safety officer for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, says nothing of the sort is going on.

"We’ve been talking about this for 16 months," White said of the rule. "We can amend the rule if necessary … I don’t see your new governor as part of this."

The rationale for taking all comers

The facility, which is designed to take radioactive materials such as contaminated clothing, glass, metal, reactor components and sludge, needs a certain amount of waste to cover the fixed costs associated with construction.

White, speaking as commission vice chair, said allowing material from other states into the landfill would lower the operating costs for the compact members tenfold.

Vanags said opening up the site to more entities will keep disposal fees at the site reasonable for Texas and Vermont. The commission hasn’t set fees for "imports," but so far it hasn’t imposed up-front contributions from noncompact waste generators. Vermont will pay $25 million to support construction of the site this year.

"The way to reduce cost per cubic foot is to increase your capacity," Vanags said in contending the only way the commission would consider "imports" would be if there is surplus capacity.

Vanags said before the commission would accept applications, it would conduct an updated study to determine how much capacity would be needed by the two compact states.

"We recognize as a commission we have to have a process (for dealing with requests)," Vanags said. "We’re not opposed to importation. We’re open to it, but as long as our capacity is protected. The facility in the future may be expanded, and they may amend their license. In future, there may be surplus capacity."

White supports expanding the site to accommodate more waste. The limitations now placed on the landfill are under the terms of the current license issued by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, White said. The site itself, he believes, could be expanded.

In the meantime, demand is high, White said. Medical waste vendors are already coming in to the state of Texas in anticipation of the facility opening a year from now, he said. Hospitals are having a difficult time disposing of waste used in research and in the treatment of cancer, he said.

"So many people say you’re opening the door," White said. "The door is already open. Waste is already coming in to Texas, and we don’t have control over where the waste is stored. We don’t have procedures to say you can’t bring it in."

CLARIFICATION: The following sentence was added to the story, 11:20 a.m. Dec. 2, 2010: David Coriell, the spokesman for Douglas, wrote in an e-mail that the governor "has said, on many occasions, he believes 60 years is too long."

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.