After the Nuclear Plant Powers Down

November 22, 2010

Peter Wynn Thompson

The New York Times

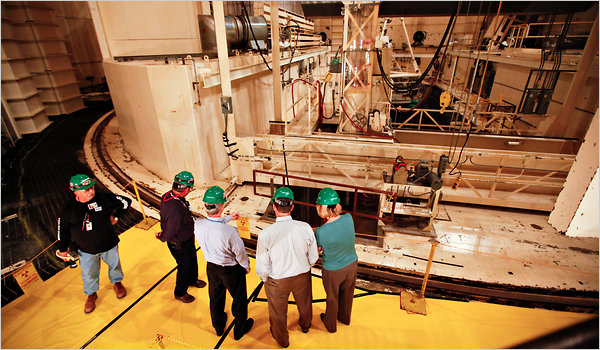

The north reactor building at the retired Zion Nuclear Power Station in Zion, Ill.

ZION, Ill. — Twelve years ago, Commonwealth Edison found itself in a bind.

The twin-unit nuclear reactor known as Zion Station has been in limbo for more than a decade, and Commonwealth Edison, now part of Exelon, paid about $10 million a year to baby-sit the defunct reactor.

The Zion Station, its twin-unit nuclear reactor here, was no longer profitable. But the company could not afford to tear it down: the cost of dismantling the vast steel and concrete building, with multiple areas of radioactive contamination, would exceed $1 billion, double what it had cost to build the reactors in the 1970s. Nor could Commonwealth Edison walk away from the plant, because of the contamination.

The result was that Zion Station sat in limbo for more than a decade, and Commonwealth Edison, now part of Exelon, paid about $10 million a year to baby-sit the defunct reactor.

Now, though, the company is trying out a radical new approach to decommissioning the plant that promises to make the process faster, simpler and 25 percent less expensive — instead of hiring a contractor, it has turned the job and the reactors over to a nuclear demolition company that owns a nuclear dump site. The cost will be covered by the $900 million that Exelon accumulated in a decommissioning fund.

If the approach is successful, it could have implications for 10 other nuclear plants around the country that are waiting to be decommissioned, and for the 104 reactors that are still in operation but will eventually be torn down. It will also save money for electricity customers, who often end up paying for the cleanup of nuclear plants through their utility bills.

The decommissioning operation at Zion, which began on Sept. 1, will skip one of the slowest, dirtiest and most costly parts of tearing down a nuclear plant: separating radioactive materials, which must go to a licensed dump, from nonradioactive materials, which can go to an ordinary industrial landfill.

The new idea is not to bother sorting the two. Instead, anything that could include radioactive contamination will be treated as radioactive waste.

Exelon could never have done this on its own, because the fee for disposing of radioactive waste was too high. But the company has given the reactor to EnergySolutions, a conglomerate that includes companies that have long done nuclear cleanups, and which also owns a nuclear dump.

"This is a first-of-a-kind arrangement," said Adam H. Levin, director of spent fuel and decommissioning at Exelon.

He added that others could do the job for less than Exelon and acknowledged, "utilities in general are not very good at tearing plants down."

Government regulations require that nuclear reactor sites be thoroughly decontaminated, so that they can be released for re-use — often a lengthy process. The plan is to return Zion’s site, in the midst of parkland on the Lake Michigan shore north of Chicago, to re-use by 2020 — 12 years earlier than expected under Exelon’s original plan, which was to begin in 2013 and finish in 2032.

Any money left over from the $900 million in the plant’s decommissioning fund goes back to electricity customers in the Chicago area.

On Sept. 1, Exelon transferred ownership, along with the license issued by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, to EnergySolutions, which is based in Salt Lake City.

The company owns a one-square-mile area of desert about 70 miles west of there, in Clive, Utah, where most of the Zion plant is supposed to be shipped. The dump in Clive already has parts of several other defunct nuclear plants — including Maine Yankee in Wiscasset, Me., and Yankee Rowe in Rowe, Mass.

In those two cases, the reactor owners tried to sort the radioactive materials from the nonradioactive, in order to dispose of ordinary concrete and steel at recycling centers or industrial landfills. It turned out to be a costly mistake, many in the industry now say.

Workers used a device like a pneumatic drill to "scabble" the concrete, knocking off the surface layer.

"It got to be very, very complicated and nasty work," said Andrew C. Kadak, a nuclear consultant who at the time was president of the company that operated Yankee Rowe. Often, he said, a survey would find that the concrete was not clean, or worse: that a tiny bit of radioactive material was mistakenly shipped to a "clean" landfill.

"It’s easier to suppose everything is radioactive," Mr. Kadak said.

Sometimes a contractor hired to decommission plants would also find radioactive material in unexpected places or at unexpectedly high levels, other experts said.

Crowds of workers would stand idle while the contractor sought the plant owner’s authorization to deviate from the procedures specified in the contract — a costly proposition at a site with 500 workers paid collectively "$30,000 to $50,000 an hour," said John A. Christian, president of the Commercial Services subsidiary of EnergySolutions.

At Rowe, managers finally gave up and shipped vast amounts of concrete, much of it clean, to the repository in Clive.

The new plan for Zion, by far the largest nuclear power plant to be decommissioned and the first twin-unit reactor to be torn down, eliminates the relationship between contractor and owner. EnergySolutions has hardly any internal cost for burial, beyond shipping.

Mark Walker, a spokesman for EnergySolutions, said that the dump could accommodate all 104 of the nation’s operating nuclear plants, "with space left over."

It could also absorb plants that are shut and awaiting decommissioning, like Indian Point 1 in Buchanan, N.Y.; Millstone 1 in Waterford, Conn.; and Three Mile Island 2, near Harrisburg, Pa., the site of the 1979 accident.

Not everyone is delighted with the idea of Exelon turning the job over to EnergySolutions.

Tom Rielly, the executive principal of Vista 360, a community group in nearby Libertyville, Ill., said that with a monopoly provider of dump space also functioning as the contractor, it would be difficult to determine what was being charged for disposal and whether electricity customers were getting a good deal.

But approval from utility regulators in Illinois was not required for the deal, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission gave its assent, so the work is going forward.

EnergySolutions cannot dispose of all the waste.

Clive is licensed only for the least contaminated material. And the spent nuclear fuel is in the same situation as used reactor fuel all over the country: the Energy Department is under contract to take it, but has no place to dispose of it.

Until a permanent repository is built at the proposed Yucca Mountain facility in Nevada or another location, the waste will stay at the Zion site in steel and concrete casks built to last for decades.

Frank Flammini, a control room operator, has worked at the Zion Station since before it shut down.

The room, filled with 1970s-style dials, used to have at least six people around the clock, but on a recent afternoon he sat alone in the control room with his coffee cup, next to the one modern piece of equipment, a flat-panel display showing the temperature, water level and humidity of the room housing the spent fuel.

Mr. Flammini, 54, said he was called on now and then to make sure equipment was "tagged out" so that workers could safely dismantle it. But hours go by with little to do.

The parking lot of Zion is so quiet these days that the raccoons and skunks have been joined by shy species like coyote.

Mr. Flammini said he knew his job here was not permanent.

"It’ll get very busy for about four years, and then it’ll go away entirely," he said.

This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. SEED Coalition is making this article available in our efforts to advance understanding of ecological sustainability, human rights, economic democracy and social justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a "fair use" of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond "fair use", you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.